Some 16 years ago, Immaculate Heart of Mary Sister Lisa Lettiere was teaching visually impaired students in Delaware – but despite her graduate-level training, there were some she just couldn’t reach, particularly one teen, and she had no idea why.

“I went into his classroom, and he acted as if he was totally sightless. He was bumping into things, he wasn’t reaching for things, he was on the lower functioning intelligence scale,” she said. “He was showing all those behaviors, yet he had an eye report saying there was nothing wrong with his eyes. That was unusual.”

Encountering “more and more kids” with the same issues, Sister Lisa began to do some homework, and soon realized many of her students suffered from a little-known but nonetheless widespread sight disorder: cortical visual impairment (CVI).

[hotblock]

Now ranked as a leading cause of childhood visual impairment, CVI requires an educational approach that is radically different from the typical pedagogy for those with other sight disorders.

And thanks to a recent grant from the Ambassador’s Fund for Catholic Education, Sister Lisa and her colleagues are providing just that — through a one-of-a-kind program in the Philadelphia region based at the archdiocesan St. Lucy School for Children with Visual Impairments, adjacent to Holy Innocents Parish in the city’s Juniata Park section.

‘A kaleidoscope with no rhyme or reason’

Unlike other sight disorders in which the actual eye is damaged, CVI results from the brain’s inability to process information gathered by the eye.

Medical events “such as stroke, seizure, brain bleed or brain tumor” can all “damage … visual pathways to the brain” and result in CVI, said Dr. Danielle Heeney, director of special education for the Philadelphia Archdiocese’s Office for Catholic Education, which operates St. Lucy School (a beneficiary of the annual Catholic Charities Appeal).

In normal vision, light is converted through the eye’s key parts — cornea, iris, pupil, lens and retina – into electrical signals that travel along the optic nerve to the brain, where they are rendered by the occipital lobe into the images comprising eyesight.

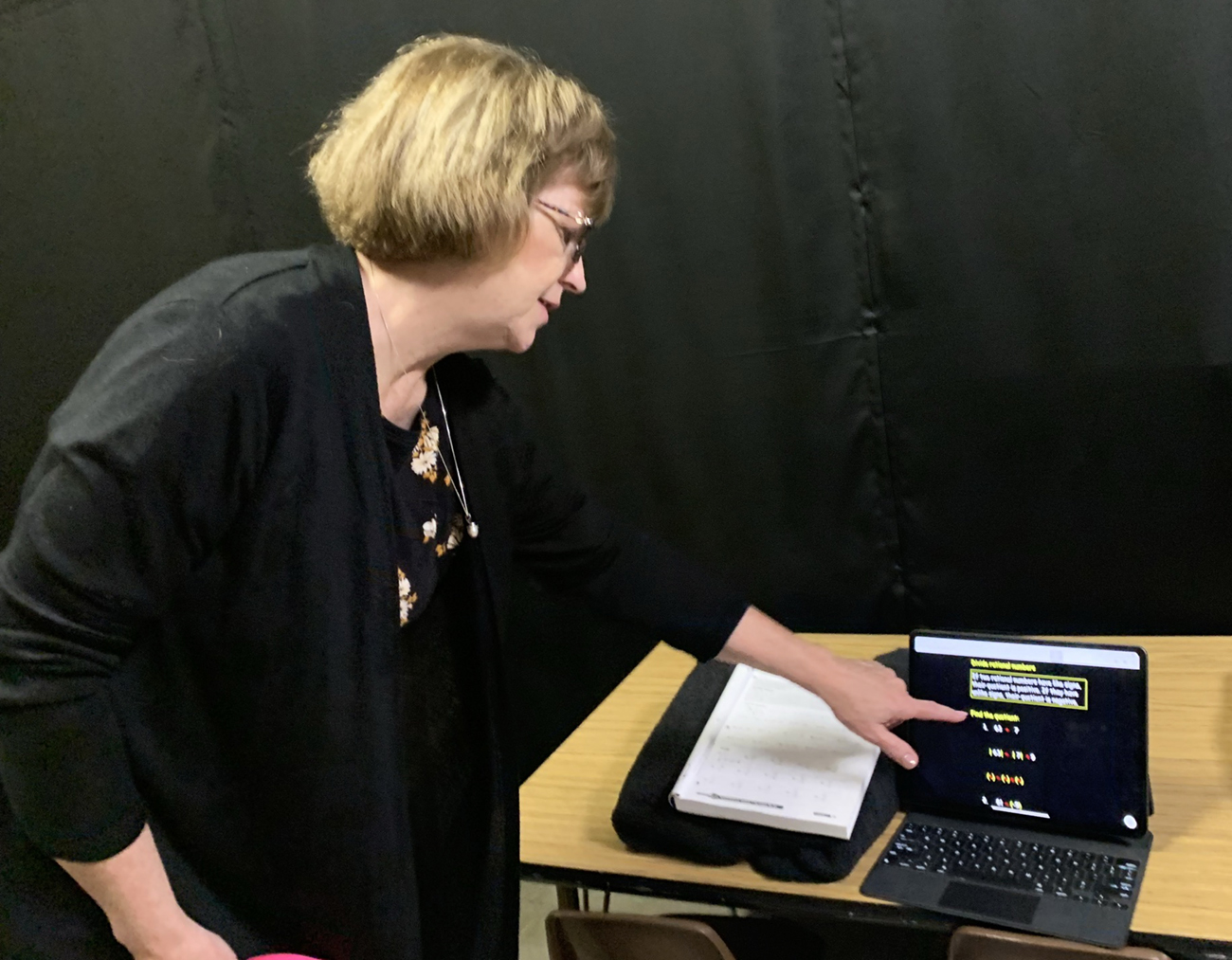

Immaculate Heart of Mary Sister Lisa Lettiere, principal of St. Lucy School, relies on dark backgrounds and bright colors such as red and yellow to simplify visual input for students with cortical visual impairment. (Gina Christian)

But for those with CVI, the light touching the world around them produces “a kaleidoscope” with “no rhyme or reason to it,” said Sister Lisa, principal of St. Lucy School. “We pretty much have to teach them how to see – how to look for the lines and the curves and the corners, and to find what we call salient features specific to a door, or a desk, or a dog.”

Faces are “very difficult” for children with CVI to decipher, said Stephanie Weinstein, whose son Noah, an eighth grade student at St. Lucy, doesn’t recognize her or the rest of his family by sight, but relies on “someone’s voice or defining features like height or color.”

Sister Lisa noted students with CVI don’t respond to traditional methods of making educational materials accessible, such as magnifying, illuminating or translating them into Braille, a writing system using patterns of raised dots read by the fingers.

Instead, CVI pioneers such as Dr. Christine Roman-Lantzy – who has specialized in the field for several decades – recommend strategies that simplify the input captured by a student’s eyes, so the brain can more effectively parse the information.

[hotblock2]

In her former Delaware classroom, Sister Lisa began by blotting out the background on which her teen student viewed materials, covering the table with a black cloth and surrounding it with a black display board.

Against the dark tones, she randomly placed objects in the two most visible colors, red and yellow, and soon her student was able to locate and organize them.

“All of a sudden, his whole world came to life,” she said.

‘A level playing field’

With a recent Ambassador’s Fund grant of $81,800, St. Lucy has launched the first year of its full-time CVI instruction program, which the fund has also committed to underwriting at the same level next year.

The support has enabled the school to hire MaryAnne Roberto, a longtime instructor for the visually impaired who also has been specifically credentialed for CVI education – a field she entered more than a decade ago, and about which she is passionate.

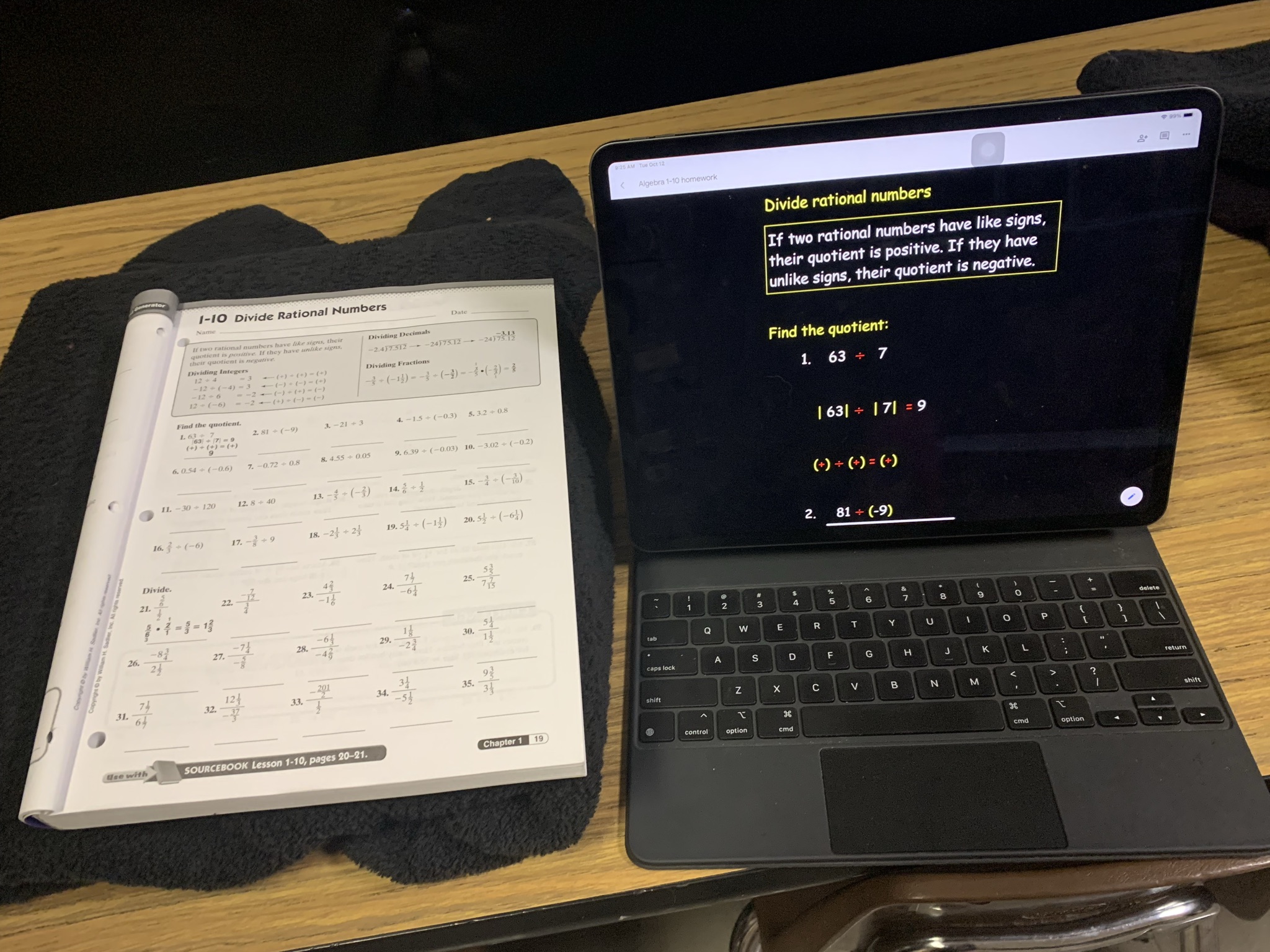

MaryAnne Roberto, St. Lucy School’s full-time, certified instructor for students with cortical visual impairment (CVI), reformats lesson material by modifying existing educational tools such as Google Docs. (Gina Christian)

Roberto ensures her students’ curriculum is “not watered down,” but rather “modified,” with a goal of “making as level a playing field as possible” for students to access educational materials.

To do so, she uses iPads and readily available online platforms — such as Google Docs, Google Slides, Boom Cards and “a few educational apps” – with “specific adaptations” tailored “very intentionally” to better serve students with CVI.

For Noah Weinstein, Roberto created a Google Docs template that replaced the default white background with one that is black, enlarged the font and doubled the line spacing. With those changes in place, she regularly scans curriculum material – “science, social studies, algebra” — and drops it into the template, making it CVI-friendly.

Adapting lesson plans for CVI-based learning can take a great deal of time, said Roberto and Sister Lisa, and most intermediate units (IUs) – regional educational service agencies that supplement public and private school resources – aren’t designed for the task, since their visual impairment teachers must travel to multiple sites on tight schedules.

Reformatting curriculum materials for students with cortical visual impairment (CVI) can take hours, said CVI -certified instructor MaryAnne Roberto. (Gina Christian)

“When I worked for one IU, I had 40 students on my case load in 13 different buildings,” said Sister Lisa.

Dedicated programs such as the one at St. Lucy, along with initiatives to broadly raise awareness of CVI, are critically needed, said both Sister Lisa and Roberto – especially since the condition is often undetected or repeatedly misdiagnosed.

Stephanie Weinstein described her son’s diagnostic journey as “complicated, with a lot of missteps,” while fellow St. Lucy parent Kristen Garrison said she didn’t find out daughter Kennedy had CVI until almost five years after her child had a stroke at birth.

Because they can become anxious, overwhelmed and withdrawn by their struggle to interpret bewildering visual input, children with CVI are often mistakenly regarding as having autism spectrum disorder, learning disabilities or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

“Shared behaviors are not shared diagnoses,” said Roman-Lantzy, who along with her colleagues urges doctors and families to test children for common CVI markers, such as an inability to recognize faces and difficulty finding their own, a tendency to stare at lights while noticing red and yellow more than other colors, and a decreased ability to maintain a sustained gaze.

Recognizing the world around them

And while CVI isn’t curable, Roman-Lantzy said children with the condition can improve their vision with proper intervention.

“I measured kids with CVI, and I sequentially began to see trends of progress that were undeniable,” she said.

Garrison said the St. Lucy program has helped her daughter become “so much better at being able to recognize” the world around her — including her mother’s face.

“The progress students make when they receive CVI-focused support is incredible,” said Dr. Heeney.

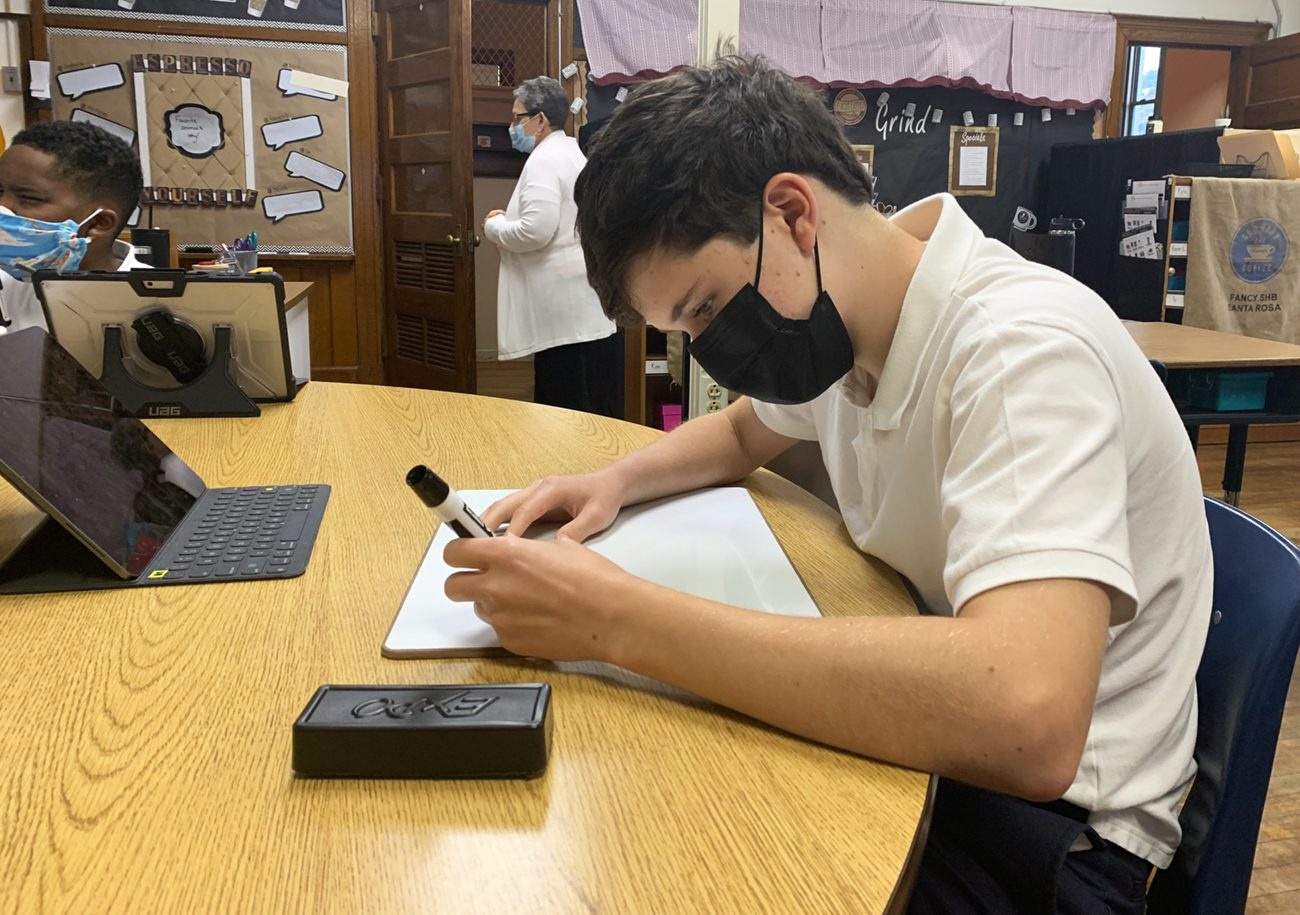

That impact extends well beyond the classroom, opening doors in every area of the children’s lives. Kennedy is set to receive her first sacrament of reconciliation and of holy Communion this year, while Noah has just celebrated his bar mitzvah, even creating a video called “How I See” for his preparation project and relying on more than 200 slides on his iPad to read the required Torah passage in Hebrew at the ceremony.

With greater confidence in their abilities, both students also enjoy their well-deserved downtime. Kennedy said she was excited to break in her new Nintendo system, while Noah plays piano, composes music and rattles off puns with a lighting wit.

“I like to throw a few jokes into the middle of the conversation,” he said with a smile, before hurrying to his next class.

Kennedy Garrison uses a black mobile desk surface and brightly colored disks during a lesson in the CVI resource room at St. Lucy School for Children with Visual Impairments. (Gina Christian)

PREVIOUS: Faithful serve hundreds of Thanksgiving meals to area families

NEXT: Hanukkah celebrates religious freedom, hope, say local Jewish-Catholic relations experts

Share this story