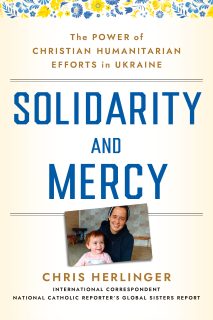

This is the cover of the book “Solidarity and Mercy — The Power of Christian Humanitarian Efforts in Ukraine” by Chris Herlinger. The book is reviewed by Matthew Gambino. (Photo courtesy Morehouse Publishing)

Unless you travel to Ukraine, it’s hard to experience the human toll of the war unleashed there by Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022.

One sees news images of smoking concrete rubble, all that is left of homes and businesses destroyed by Russian missiles and bombs.

Missing are the broken bodies of the dead, the burns and injuries of the maimed, the unseen mental trauma of the displaced.

Also unheralded are the generous souls near and far who help Ukrainians cope with a war they did not invite yet struggle to endure.

Stories of hope, on the part of survivors and the religious sisters, clergy and humanitarian workers serving Ukrainians, are the subject of a remarkable book published this month, “Solidarity and Mercy” (Morehouse Publishing, 2024, $29.95; pp. 232).

Author Chris Herlinger, a reporter with National Catholic Reporter newspaper, traveled to Ukraine from 2022 to this year to witness “the power of Christian humanitarian efforts” in the country, as the book’s subtitle states.

“Solidarity and Mercy” makes considerable effort to explain the context of a conflict that stretches past 2022, past Russia’s 2014 annexation of Ukrainian Crimea and even past the genocidal Holodymyr of the 1930s. That famine forced by Soviet policies resulted in the starvation deaths of millions and displacement of millions more.

As Herlinger reports, the memory of centuries of cultural and linguistic domination by Russia against its western neighbor form the basis of resistance by Ukrainians in the current conflict.

Hope and the conviction that their fight for freedom is demanded by history inspire Ukrainians’ confidence in eventual victory.

The strong fight for it, while the vulnerable – the elderly, children and their caregivers — flee combat zones for relative safety, where they find compassion from Greek and Roman Catholic religious sisters and lay humanitarians.

These are the stories that Herlinger brings to light in his reporting.

Fueled by recitation of the rosary, Dominican Sister Margaret Lekan and a volunteer drive six hours by car from southeastern Poland across the western Ukraine border to bring candles, flashlights and fresh bread – then 12 hours back, facing a jammed border crossing.

Simple items such as these are hard for internal refugees to obtain or are costly, which makes them prized gifts in buildings with intermittent electricity.

While early sections of the book trace the author’s travels from refugee resettlement areas in Poland to Ukraine and its capital Kyiv, the reports from Zaporizhzhia in the east underscore the particular hardships of life in a combat zone.

Poor rural villagers Yurii and Inna Sirinok typify many who have lost their home to bombing. In a country with a scant social safety net, losing one’s residence means one’s best tangible asset is gone too.

“We’ve lost everything” is a phrase repeated throughout the book by people across the country.

Living now with friends in another village only five miles from the front line, Inna said she lives in fear, “scared all of the time.”

Compounding the couple’s plight is the difficulty elderly people face in rebuilding their home and their life. “We don’t have the strength,” Yurii said, as his wife exhibited loss of memory and disorientation – signs of war trauma – when discussing their situation.

A Caritas Ukraine official estimated that 2 million homes have been destroyed. Archbishop Boris Gudziak, Metropolitan Archbishop of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia and a native of Ukraine, estimated some 14 million residents have been displaced.

In an interview with Herlinger appearing in the appendix, Archbishop Gudziak traces the spiritual underpinnings and moral imperative of continued resistance to the invasion of his home country with words of encouragement and hope.

Despite its brutality, the war appears in these pages only to have strengthened the resolve to continue fighting for a free and independent Ukraine.

The book’s subjects admit weariness but emphasize consistently that Ukraine will prevail in the war. From the humblest villager to the highest prelate, they reject any compromise peace agreement.

This solidarity, made apparent across the span of the book, is amplified by people of good will across Europe and the United States who have taken in refugees and sent donations of food and supplies – not to mention ample supply of military weaponry, gear and ammunition.

For his part Herlinger presents stories of mercy and solidarity well.

Not so convincing is his inclusion in a late chapter of arguments by American pacifists for negotiations that might result in a cessation of hostility.

While Ukrainians would welcome a cease fire, skeptics point out that it would be temporary as Russia would regroup, solidify its territorial gains and continue to brutalize Ukrainian citizens in their own country.

They argue that a peace treaty conceding gains won by military force would not only fail to achieve peace in Ukraine, but would embolden similar aggression by Russia against its smaller neighbors.

“Solidarity and Mercy” ends on a high note with the insights of Slovakian Dominican Sister Lydia Timkova, who despite many hardships, joins with the Ukrainians in solidarity as she serves in prayer and religious education.

Her work of loving service – a definition of mercy — is all part of God’s plan, she believes.

“I’ve dedicated my life to God, to helping people,” she said. “And now I am feeling the living God. He gives me power.”

PREVIOUS: Delco pastor’s book on angels shows they’re ‘down to earth,’ leading us to heaven

NEXT: Personal Suffering Leads Filmmaker to Tell Story of Saint of Auschwitz

Share this story