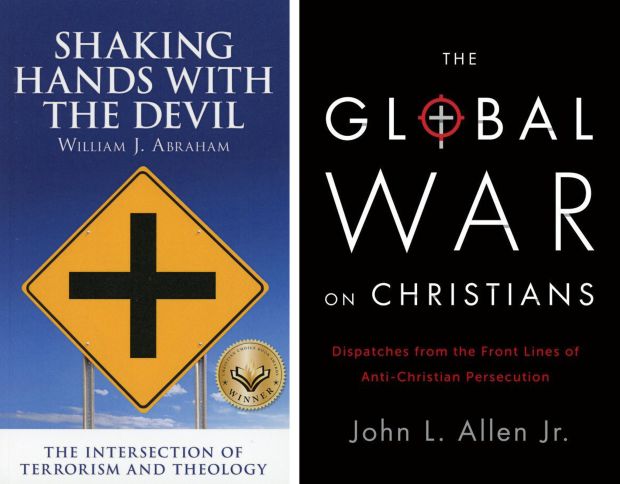

“Shaking Hands With the Devil: The Intersection of Terrorism and Theology”

by William J. Abraham.

Highland Loch Press (Dallas, 2013).

180 pp., $19.95.

“The Global War on Christians: Dispatches From the Front Lines of Anti-Christian Persecution”

by John L. Allen Jr.

Image Books (New York, 2013).

336 pp., $25.

Like it or not, religion has always taken a central place in the world’s violence. While William Abraham’s “Shaking Hands with the Devil” and John Allen’s “The Global War on Christians” discuss very different issues, the authors share the same aim of reducing the stereotyping about religion and the religious that seems a constant in our secularized world.

Having grown up in Northern Ireland and witnessed the violence firsthand, Abraham points out many common fallacies, such as the assumption that the violence in Northern Ireland is religiously based, when in fact it is an ethnic issue.

This sectarianism divides “Protestants,” mostly atheists who identify with the United Kingdom, from “Catholics,” who dream of a united Irish republic.

[hotblock]

Abraham is more philosophical and theological than political. He avoids taking sides, and sees the people as caught up in a process that is beyond them. Readers won’t be confronted by moralizing of any sort. Rather, he muses about the nature of violence, religion and human behavior.

While Abraham only touches on the just war theory made famous by St. Augustine, he offers much more balance to this important topic than Christian pacifists, whom he rejects as parasites living under the peace provided by those willing to fight for justice and defend the weak.

He writes scornfully of the famous American Christian theologian Stanley Hauerwas: “His reductionist and simplistic descriptions of war are so obviously false that they undercut his claim to possess an exclusively privileged access to the truth about war through the church.”

Abraham’s treatment of Islamic terrorists echoes the entirety of the book in searching for nuance and honesty rather than platitudes. He does ask if Islam itself is the problem, something that the mainstream media and the governments of the West shy away from doing. He notes how devout the 9/11 terrorists were, including the religious preparations that they likely undertook just before they acted.

Readers who are used to weak-kneed Christian leaders will be satisfied with the author’s frankness.

“The Global War on Christians” offers a stark assessment of the facts gathered by Allen. The book is a wake-up call to comfortable Christians who have no idea how bad things are, even in the United Kingdom or North America. He quotes Chicago Cardinal Francis E. George’s chilling words: “I expect to die in bed, my successor will die in prison, and his successor will die a martyr in the public square.”

All areas of the world, including the Catholic countries Mexico and Brazil, have seen Christian martyrdom in recent years. Christians following the dictates of their conscience have often run afoul of local ranchers and government officials in the Amazon area, for instance. Often such believers are putting into action the teachings of Catholic social justice by fighting for the dispossessed.

Filling the book with anecdotes puts a human face on the suffering of so many. We read of a Honduran pastor who was shot while walking his dogs, two days after the daughter of another pastor had been killed.

While discussing these sad episodes, Allen outlines a more precise definition of martyrdom than we commonly imagine: “Observers believe the pastors were not targeted because they were Christian, but were victims of robberies. Their choice to remain accessible in the environment, however, reflected a determination to live the Gospels despite obvious risks.”

An optimist, Allen adopts Tertullian’s famous phrase, “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church,” meaning that martyrdom leads to church growth. Yet this is a weak argument: Centuries of Christian martyrdom in Muslim countries have only brought a numerical and cultural decline of Christians in that area, however dedicated the small minorities remain. Likewise, formerly religious countries that fell under communism, such as the Czech Republic or Bulgaria, are largely atheist after decades of church persecution.

It is also an unconvincing argument because Allen fails to discuss the possibility that rapid church growth precedes and in some way provokes increased martyrdom, rather than the opposite. A swelling number of Christians invites persecution because believers are more visible than previously and are perhaps seen as a menace by political authorities who have often based their power on traditional social structures.

In any case, while both books are worth the effort, Allen’s is the one people will read to the last page, principally because of how timely it is and because of his references to real people.

***

Welter has degrees in history and theology, and teaches English in Taiwan.

Share this story