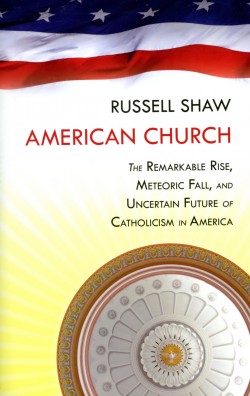

“American Church: The Remarkable Rise, Meteoric Fall and Uncertain Future of Catholicism in America”

“American Church: The Remarkable Rise, Meteoric Fall and Uncertain Future of Catholicism in America”

by Russell Shaw.

Ignatius Press (San Francisco, 2013).

233 pp. $16.95.

Russell Shaw takes on the daunting task of chronicling Catholic Church history in the United States in “American Church: The Remarkable Rise, Meteoric Fall and Uncertain Future of Catholicism in America.”

As the book title indicates, he tends toward pessimism. He sees the decline and fall principally as the result of efforts by influential church leaders in the19th and 20th centuries to assimilate the church into U.S. society, leading to the watering-down of belief in many traditional Catholic teachings, such as on abortion and artificial birth control, as many Catholics fell victim to the views and attitudes available in a pluralistic environment.

Another important factor in the decline, argues the book, is a sharp division of the U.S. church after the Second Vatican Council into what Shaw calls the “conservatives” and “liberals” fighting to interpret the council teachings according to what they want the church to be. Shaw clearly favors the conservatives.

The author is in a good position to write about the U.S. church. For 18 years he was the spokesman for the U.S. bishops’ conference (the then National Conference of Catholic Bishops/U.S. Catholic Conference). He also has written numerous books and articles on the church as a free-lance writer. So he knows the church from the inside out and the outside in.

The book, however, falls into the contemporary mindset of polarizing issues and throwing them into a culture wars framework. So it sees the 1800s as primarily marked by the struggles between church people fighting assimilation into a secular culture and those wanting to assimilate at the risk of watering-down Catholic faith and identity. Likewise, the post-Vatican II period to the present is defined by the splits over the council.

Such an approach leaves little room for gray areas. It sidesteps the unique circumstances presented to the church in the 1800s by the U.S. as a new nation looking for its political feet as the pioneer in developing a democratic form of government. This new government also was pledged to the novelties of church-state separation and freedom of worship for all religions. Church leaders needed a trial and error period to thrash out how to function within such a framework.

Shaw also doesn’t examine the cross-fertilization. The American experience has had important positive influences on the U.S. and universal church in terms of developing a theology and policies for dealing with a pluralistic religious society. Probably the most important result is Vatican II’s Declaration on Religious Freedom championed by the U.S. bishops with much of the drafting done by American Jesuit Father John Courtney Murray. Other examples include ecumenism, interreligious dialogue and the social comportment of the church in modern pluralistic societies where it is only one of many moral and ethical voices trying to shape public policies.

When the church has found common ground with other religions and secularists on issues such as civil rights and war and peace it has had a significant impact shaping U.S. government policies and national attitudes. On abortion, where common ground is slim, the record is far from good.

As Shaw cites, the U.S. church is facing statistical declines in the number of regular churchgoers and parishes. Vocations are certainly not in keeping with the needs of the Catholic population. But blaming this mainly on efforts to assimilate into mainstream society is misleading.

At the same time, the book has positive values. It introduces U.S. Catholics to some of the Catholic giants of the 1800s such as Orestes Brownson, Paulist Father Isaac Hecker and Cardinal James Gibbons. They grappled with the issues of dealing within a new political and social system, not always in agreement and not always with success.

Regarding contemporary issues, whether Catholics consider themselves “liberals” or “conservatives” most could easily agree with Shaw that if the church is to grow and be influential, it has to avoid secrecy and clericalism.

***

Bono is a retired CNS staff writer.

PREVIOUS: Hi yo, moviegoer, and ride away from this ‘Lone Ranger’

NEXT: Movie review: Despicable Me 2

Share this story