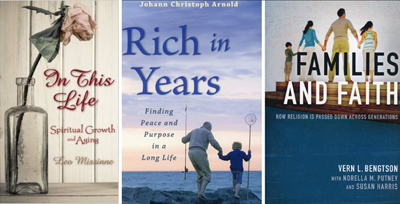

“In This Life: Spiritual Growth and Aging”

“In This Life: Spiritual Growth and Aging”

by Leo E. Missinne.

Liguori Publications (Liguori, Mo, 2013).

112 pp., $8.99.

“Rich in Years: Finding Peace and Purpose in a Long Life”

by Johann Christoph Arnold.

Plough Publishing House (Walden, N.Y., 2013).

161 pp., $12.

“Families and Faith: How Religion Is Passed Down Across Generations”

by Vern L. Bengston with Norella M. Putney and Susan Harris.

Oxford University Press (New York, 2013).

267 pp., $29.95.

Spend any time with the aging and you will discover that one thing they have in common is personal stories.

It makes sense that the longer one has lived, the greater repertoire of material he or she will have. And, as life expectancy increases, one can expect a greater supply of stories. Collectively, these three books add to the story storehouse, but each in a different way and for a different purpose.

“Rich in Years” by Johann Christoph Arnold is for those for whom more of life is in the rearview mirror than in the windshield. Arnold offers an opportunity to engage with people who are immersed in their faith and who relied on it through sickness and as they anticipated death. These are upbeat, inspirational stories that — if read with an open heart and mind — have the potential to change, for the better, how readers live their remaining years.

[hotblock]

Cancer survivors, a reformed prisoner, a woman who lived for 45 years as a widow — these are some of the people who provide the encouragement, who ask questions about mending broken relationships, seeking and granting forgiveness from those they’ve hurt and who have hurt them, and who express gratitude to God for the lives they’ve had.

Arnold features people with inspirational stories, and they, with his help, tell them in an engaging manner that readers, especially aging readers, will appreciate.

Leo Missinne’s “In This Life” is a pep talk for the aging, as he notes, “Old age is not a problem but a possibility.” To that end, he writes about life’s meaning, its purpose, the role of suffering and how faith encompasses all of it. The pages are filled with statements on purpose, suffering and faith that can be material for reflection and prayer:

“Meaninglessness is manifested in the disease of our time — boredom.”

“Happiness and suffering are like love and hate. They are not opposites; they are components of the same reality.”

“Christians know that God never abandons a suffering human being.”

Missinne uses a pastoral tone in speaking to readers about what may be of concern to them. He concludes with “Ten Commandments for a Successful Old Age,” that is an excellent examination of conscience; also included are prayers related to aging.

Given the topics “In This Life” covers and the ideas its presents, the aging will welcome it, as will ministers to the aging who will find it a valuable resource to share and discuss with those to whom they minister.

In the conclusion to “Families and Faith,” Vern Bengston, Norella Putney and Susan Harris state, “This project started out as a traditional academic study, with hypotheses and data analyses that could be published in scholarly journals.” Thirty-five years’ worth of academic study — 1970-2005.

The nine chapters preceding the conclusion are academic nourishment for graduate students and doctoral candidates discussing the findings and sipping cappuccinos. They will, no doubt, feast on the data provided by the Longitudinal Study of Generations, which comprises more than 3,500 storylike responses, from members of 357 three- and four-generation families.

However, as the authors note, what they discovered “has practical implications as well.” That’s the reward for readers who are not adept at devouring data and who are unfamiliar with the “literature” in this field of research.

In the preface, the authors state that the book “addresses three major questions”: To what extent are parents passing on their faith in today’s rapidly changing society? Have the many social and cultural changes of the last half-century eroded the ability of families to transmit religion from one generation to the next? Why are some parents successful at passing on their faith while other parents are not?

Despite being a heavily academic work, the answers to these questions are expressed in language that readers, particularly parents who might be guilt ridden by their children’s choices — or lack thereof — when it comes to religious practice, will understand.

Besides letting parents know how and why they were successful or unsuccessful in passing on the faith, the conclusion contains a section titled, “What Can Clergy and Religious Leaders Do?” within which the authors provide a reminder to church leaders: Catholic priests and mainline Protestant ministers “might have had the greatest cause for alarm; in our sample, only 4 in 10 Catholic parents had young adult children indicating they were Catholic, and for mainline Protestants the figure was just 3 in 10.”

For all of its academic weightiness, the findings reported in “Families and Faith” can be useful for those seeking formulas for and guidance in threading religious beliefs across generations. Families attempting to foster denominational continuity and churches trying to maintain membership could both benefit.

***

Olszewski is general manager of the Catholic Herald, the publication serving the Catholic community in southeastern Wisconsin.

PREVIOUS: Cancer-themed teen drama delves into love, death and tears

NEXT: ‘Groundhog Day’ goes sci-fi thriller in ‘Edge of Tomorrow’

Share this story