NEW YORK (CNS) — “Timbuktu” (Cohen Media Group) offers one of the most gently lyrical and original portrayals of withstanding tyranny ever shown.

The oppression comes at the hands of jihadists who occupied northern Mali, imposing sharia law based on a fundamentalist reading of the Quran. They’ve banned music and soccer. Bullhorn-wielding “enforcers” with pickup trucks and motorcycles harass and arrest violators.

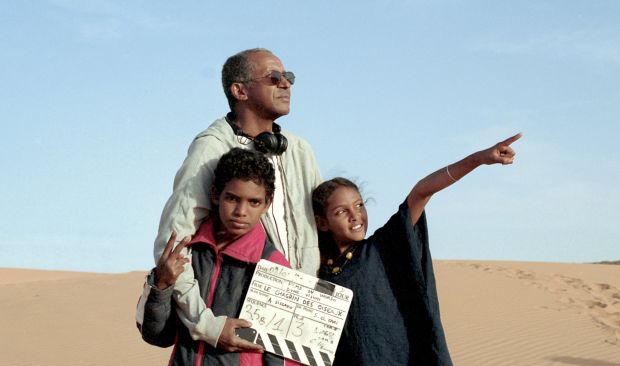

Director Abderrahmane Sissako’s camera lingers on a group of young men, warmed by the midday sun, defiantly and joyfully playing soccer. Or so it seems.

[hotblock]

There’s no ball. They’re just pantomiming a game, getting full enjoyment out of it as they jostle in formations and celebrate “goals.” When the enforcers drive past, the players mutely perform calisthenics.

“No, it’s not based on a real incident,” Sissako, speaking French, explains through an interpreter. “But since my film talked about three things — what is forbidden, what is justice and our way of looking at women during a jihadist occupation — I thought about how cinema would show that.” He thought the game “a form of collective resistance.”

Most of “Timbuktu,” an Academy Award nominee for Best Foreign Language Film, is based on events occurring in early 2012. That’s when ethnic Tuareg rebels, assisted by the Islamist group Ansar Eddine, known to be linked to al-Qaida, overran parts of Mali, a landlocked nation in western Africa.

Their goal was to establish a separate state. The French military expelled the jihadists the following year.

Catholics comprise less than 2 percent of Mali’s predominantly Muslim population of 15.3 million. Archbishop Jean Zerbo of Bamako and Catholic Relief Services delivered humanitarian aid for displaced persons in the aftermath of the military action.

Jay Weissberg, praising “Timbuktu” for the trade paper Variety, wrote that the film “confirms his (Sissako’s) status as one of the true humanists of recent cinema.”

The director forgoes awkward political debates to show the occupation’s impact on a tent-dwelling herdsman, Kidane (Ibrahim Ahmed). Kidane is devoted to his wife, Satima (Toulou Kiki), his 12-year-old daughter, Toya (Layla Walet Mohamed), and to Issan (Mehdi A.G. Mohamed), an orphaned boy the family has taken under its wing.

Mali has a long tradition of tolerance. So at first, the locals resist their young occupiers with simple refusals. A half-dozen jihadists storm into a quiet mosque during prayers. The imam (Adel Mahmoud Cherif) reminds them they can’t enter a mosque wearing shoes and toting guns.

“But we can,” one replies. “We’re doing jihad.”

The imam is unimpressed: “Please leave.” So they do.

Another jihadist insists that Satima must keep her hair covered. “If he dislikes it, he shouldn’t look at it,” she retorts. An angry fishmonger in a market dares the men to cut off her hands for not wearing gloves while she works. They back away.

[hotblock2]

Sissako also displays the occupiers’ hypocrisy — banning soccer games even as they eagerly discuss their favorite teams and players. Silencing music sometimes confuses them: “I found out where the music’s coming from,” one jihadist tells the others. “They’re singing praise to the Lord and his prophet. Shall I arrest them?”

The true horror arrives after Kidane is arrested and sentenced to death for slaying a fisherman who killed one of his cattle. A couple whose only crime was having relations out of wedlock are buried in the sand up to their necks and stoned.

Young girls are forced into marriages. Fatou (Fatoumata Diawara), a singer, croons softly in protest, without screaming in pain, as she receives 40 lashes for the crime of making music.

Sissako, who co-wrote the film with Kessen Tall, was born in Mauritania, educated in Mali, and now divides his time between his homeland and Paris. Sissako filmed “Timbuktu” mostly in Oualata, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Mauritania he calls the titular locale’s “twin city.”

How does Sissako think his measured presentation can counterbalance such desperate acts as the Charlie Hebdo slaughter in Paris and murders by Islamic State fighters in the Middle East?

“I believe that when you want to tell about violence, it’s important not to show violence as a spectacle,” he says. “Showing violence in a spectacular way makes violence banal. I don’t need to see five liters of blood to know that a person is dead.”

He explains, “Art always needs to create a respectable distance when it wants to evoke something. (The film is) a protest against violence, barbarity and terrorism.”

Is it also, in any way, an expression of his personal religious faith? The question, one so blithely asked by Americans these days, takes him aback: “I find that to be a somewhat delicate question — because I think faith is a personal matter. To bring it up to other people, personally, it disturbs me,” Sissako replied.

“What interests me is a person’s ability to defend human values. These values belong to every religion.

“I have a humanist point of view. That’s what really interests me. A gaze is neither Christian nor Muslim. It’s just a gaze, that’s all.”

***

Jensen is a guest reviewer for Catholic News Service.

PREVIOUS: New-breed British knights look hip, but turn gruesome

NEXT: Movie review: Hot Tub Time Machine 2

Share this story