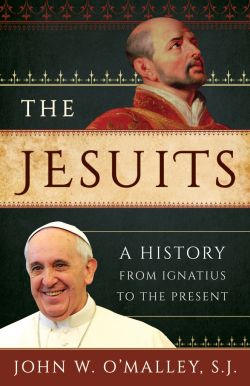

“The Jesuits: A History From Ignatius to the Present”

“The Jesuits: A History From Ignatius to the Present”

by Father John W. O’Malley, S.J.

A Sheed and Ward book published by Rowman and Littlefield (Lanham, Maryland, 2014).

129 pp., $22.

With the 2013 election of history’s first Jesuit pope, interest mounted exponentially in the now-worldwide Society of Jesus that St. Ignatius Loyola, with nine friends, founded in the 16th century.

What Pope Francis’ election means for the Jesuits “remains to be seen,” writes Jesuit Father John W. O’Malley. But he points out in “The Jesuits” that “having a Jesuit as pope” represents “an eventuality that through the centuries seemed almost unthinkable.”

The reasons it virtually was unthinkable are, from one perspective, what Father O’Malley’s brief, easy-to-read history of the Jesuits is about. Over the course of time, “myths and misunderstandings about the Jesuits” entered so deeply into the public mind that “they seem impossible to eradicate,” he observes.

Histories of the Society of Jesus written over the centuries often reflected a certain “bifurcation.” Either the “Jesuits were saints” or they “were devils,” according to Father O’Malley. Only about 20 years ago, he notes, did historians begin “approaching the Jesuits in a more evenhanded way, asking the simple and neutral question, ‘What were they like?'”

[hotblock]

Father O’Malley’s book does “little more than glide over the surface of a long and complex history,” he informs readers. True, its pages move along rapidly from one stage in this history to another. What amazes me, though, is how much this little book accomplishes.

Readers unfamiliar with the Jesuits’ often turbulent history — especially from the time of its 1773 suppression under Pope Clement XIV to its 1814 restoration under Pope Pius VII — will feel well served by Father O’Malley. He terms the suppression a “tragedy,” not only for the Jesuits but “for the church at large.”

The Society of Jesus had become the church’s “single greatest intellectual asset.” But suppression meant its “libraries were dispersed.” Moreover, a “network of more than 700 schools closed or passed into secular hands.” At that time, Father O’Malley writes, “the Jesuits were as a body the most broadly learned clergy in the church, no matter what may have been the limitations of their intellectual culture.” Thus, suppression constituted a loss.

A fascinating, brief section of this book recalls the surprising role in the Jesuits’ ultimate survival of Russia’s Catherine the Great, who refused to implement Pope Clement XIV’s suppression decree. Father O’Malley writes, “She appreciated the contribution the Jesuits made to cultural life, and, imperious person that she was, she saw no reason to implement in her empire a decree from a foreign government.”

While this book draws into sharp focus the distressing moments of Jesuit history, it is noteworthy too for its discussion of the Jesuits’ unique contributions to the church’s life, particularly through their missionary focus, highlighted for many by the Asian ministry of St. Francis Xavier, and by their establishment of schools in so many nations.

By committing the Society of Jesus “to formal schooling as its primary ministry,” St. Ignatius and his closest advisers “took a momentous step.” Within about a decade of their founding “the Jesuits began to operate schools for lay students, something no religious order had ever done before in a systemic way,” says Father O’Malley.

Through their schools the Jesuits would be “drawn into aspects of secular culture in ways and to a degree unprecedented for a religious order.” This meant ultimately that Jesuits would serve the church and society “as poets, astronomers, architects, anthropologists, theatrical entrepreneurs and much more.”

Father O’Malley is a theologian at Georgetown University in Washington. He is the well-known author of books and articles devoted not only to Jesuit history but to the Second Vatican Council and other topics.

Twenty-five years from now the Jesuits will celebrate the 500th anniversary of their founding. What might change between now and then?

Today the order faces a priestly vocations decline in the West, while the number of men entering the order “in other parts of the world, though sometimes relatively small, has grown or remained stable.” Father O’Malley adds, “The areas of growth have been Africa and Asia, most especially India.”

The order also now is reaping the rewards of an “intense study of Jesuit sources,” he explains. This effort reveals, for example, that St. Ignatius was “a farsighted leader, a man altogether different from the prevailing stereotype of him as a martinet enforcer of military discipline in the army of Jesuit crusaders.”

Father O’Malley believes that the Society of Jesus is “evolving in new ways in a world that seems to be evolving even faster.” So the order’s challenge, “as always,” will be “to retain its identity while at the same time exploiting its tradition of adaptation to persons, places and circumstances.”

***

Gibson was the founding editor of Origins, Catholic News Service’s documentary service. He retired in 2007 after holding that post for 36 years.

Share this story