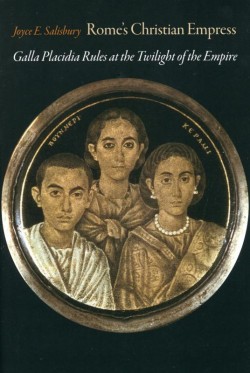

“Rome’s Christian Empress: Galla Placidia Rules at the Twilight of the Roman Empire”

“Rome’s Christian Empress: Galla Placidia Rules at the Twilight of the Roman Empire”

by Joyce E. Salisbury

Johns Hopkins University Press (Baltimore, 2015)

236 pp., $34.95

For the most part, readers of “Rome’s Christian Empress” see mere glimpses of this fifth-century member of the Theodosian imperial line, whose different family branches ruled both Ravenna and Constantinople for a few decades.

Author Joyce E. Salisbury makes the best out of what she calls the “wisps of historical evidence in buildings, laws and letters.” Salisbury spends much time giving the background to Placidia’s life. This makes the book an excellent general introduction to the first half of the fifth century, when St. Augustine was working out theology to explain the empire’s decline brought about by Germanic tribes and the generals’ infighting.

An imperial biography requires the author to focus on politics and military affairs. Yet we also get a good sense of how closely the personal lives of the imperial family, including their Christian beliefs, affected political and military intrigue.

[hotblock]

The author, professor of history at the University of Wisconsin, engages in much scholarly speculation. While the lack of materials makes this necessary and reasonable, sometimes the book ventures into fiction, as when the author claims that Emperor Valentinian’s poor choices and weakness, including his mismanagement of the powerful general Aetius, stemmed from the lack of his mother’s wise counsel, as she had passed away. Little evidence proves that he had ever listened to her much, and speculating about better decisions had she been alive is baseless.

One thing needing no speculation is Placidia’s heavy involvement, along with other royals, in the never-ending theological disputes generated mostly in the Greek-speaking East, for which the Eastern emperors called councils at Ephesus and Chalcedon. Regarding the Monophysite rejection of Christ’s dual nature, Salisbury outlines how the Theodosians’ involvement made the theological political.

When the Eastern emperor, a Monophysite, died from a horse fall, his Orthodox wife took charge of theological matters: “Pulcheria immediately moved to overthrow the ‘robber synod’ of Ephesus, and in 451, a new council was called at Chalcedon, a city near Constantinople. … From 451 on, Orthodox churches of the East and West celebrated … that both natures of Christ -– human and divine -– ‘are united without change, without division and without confusion.'”

With no concept of church-state separation, emperors brokered theological deals among the quarrelsome clergy and the hooligans who went so far as to kill Constantinople’s Orthodox bishop Flavian in 449. The author, though focused on Placidia’s life, skillfully navigates these religious issues without bogging the reader down in theological minutia.

Salisbury uses the doctrinal disputes and church history in general to build a mostly solid account of Placidia’s latter decades despite the author’s projection of much feminist idealism onto this seemingly “pious, practical, patient and politically astute” empress. The author fails to find much direct evidence to prove these qualities.

Though referred to only a few times, the most interesting theme of the book outlines Placidia’s role in the development of the devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary: “Of the churches that were built from the time of Constantine in the early fourth century through the turn of the fifth century, no church in the West was dedicated to Mary; all were dedicated to saints, apostles, or … to the Holy Cross. By the 12th century, all cathedrals in Europe were dedicated to Mary, and the beginning of this huge shift in piety came during the reign of Placidia and the eastern empresses,” Salisbury observes.

Disputes regarding the nature of the Incarnation and the role of Mary as “theotokos” found some resolution during the empress’ life, and Placidia built churches, including Rome’s Basilica of St. Mary Major, devoted to the mother of God. Interestingly, the interior mosaics portray the Virgin not as a poor Palestinian woman but as an imperial princess, perhaps not so coincidental and perhaps indicating once again the important ties between theology and politics.

This book succeeds at showing the empress’ theo-political vision and how she brought that about in her own policies and religious practices.

***

Welter has degrees in history and theology, and teaches English in Taiwan.

PREVIOUS: Movie review: Jem and the Holograms

NEXT: Comedy is a casualty of ideology in ‘Our Brand Is Crisis’

Share this story