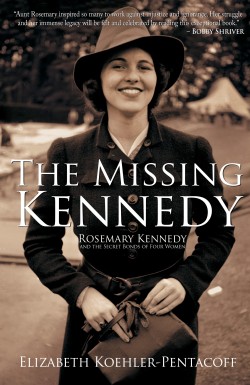

“The Missing Kennedy: Rosemary Kennedy and the Secret Bonds of Four Women”

“The Missing Kennedy: Rosemary Kennedy and the Secret Bonds of Four Women”

by Elizabeth Koehler-Pentacoff.

Bancroft Press (Baltimore, 2015).

258 pp., $27.50.

The story of young Rosemary Kennedy (1918-2005), the first daughter born to the celebrated Boston family, invites sad contemplation of what might have been. One wonders if things would have turned out quite differently for the younger sister of President John F. Kennedy, who at age 7 was diagnosed as intellectually disabled (or “mentally retarded,” as it was then termed), if during her delivery the nurse had not directed Rosie’s mother to close her legs and thus delay delivery for some two hours until the attending physician could arrive.

Some have suggested that the doctor’s tardy arrival ultimately deprived the infant of oxygen, resulting in permanent disabilities, though this cannot be proven.

And what if Rosie had not, at age 23, been subjected to a botched lobotomy by her father who was convinced that it would help her live a more “normal” life?

[hotblock]

Despite Rosie’s apparent slowness in learning, she was a sweet, lovable child whom the entire family supported with kindness and patience. She grew into a beautiful young woman, tall, vivacious and graced with a dazzling smile.

But with puberty came emotional outbursts and then sneaking out at night to meet men for sex. When thwarted, Rosie threw tantrums that were increasingly disruptive. “Because of their high profile in politics and society,” the author writes, “the Kennedys couldn’t risk the shame of sexual disease or an out-of-wedlock pregnancy.”

Without telling anyone in the family, not even his wife Rose, Joseph Kennedy subjected his daughter to a prefrontal lobotomy in 1941 that left her much worse — incontinent and incoherent. She even had to learn to walk again.

But the heart of the book is the story of Rosie’s meaningful life at St. Coletta in Wisconsin, a Catholic home for the developmentally disabled, where she lived out her life under the extraordinary care of Sister Paulus (Stella) Koehler (1910-1996), the author’s aunt.

Caregiver, chauffeur, advocate and most of all friend, Sister Paulus (a Sister of the Third Order of St. Francis of Assisi) devoted 35 years to helping Rosie, despite her many daily challenges, blossom. A prayerful, insightful, and compassionate soul, Sister Paulus seems to represent the very best traditions of the religious life. The author had access to her aunt’s private notes, which, enriched by research at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and elsewhere, offer an authoritative and detailed look at the life of the one Kennedy who has always been the least known.

It was only after 20 years that Rose Kennedy and the rest of her family first learned about Rosie’s lobotomy. After Joseph Kennedy’s stroke disabled him in 1961, Rose began to oversee Rosie’s affairs and starting in the early 1960s, the Kennedy family began to have regular visits with Rosie. (They had been kept away for two decades by strict medical advice that any family visitors would prove too emotionally disruptive.)

[hotblock2]

It was around then that young Elizabeth Koehler (born in 1957) began to go on family visits to her aunt, Sister Paulus, and Rosie. The author’s girlhood reminiscences of visiting Rosie and her family stories add a unique dimension to her book as do the many photos of Rosie enjoying her life with Sister Paulus and the nuns at St. Coletta and seeing visitors such as Rose Kennedy, Eunice Kennedy Shriver and her son Anthony Shriver, Ted Kennedy and Jean Kennedy Smith.

Koehler-Pentacoff alternates the narratives of two families, the Kennedys and her own, noting some of the common threads of mental illness and disability that can strike any family whether wealthy and prominent or more humble. This organization is sometimes jerky and disorienting.

The book’s value lies in its revelations about an essential part of the Kennedy family history that has long been unknown. Did Joseph Kennedy truly want to put his daughter away “because her behavior was tainting the family’s reputation and would hurt his career, as well as the social and political prospects for his sons,” as some have charged?

Koehler-Pentacoff sheds light on this through an interview she conducted with his grandson Anthony Shriver, who views the patriarch’s motives differently: “The experts in the field recommended (the lobotomy) to give her a more peaceful and productive life. He had a relentless desire for all of his children to be the best and to give them the best. …The goal was to enhance her life.”

Although many aspects of Rosemary Kennedy’s life story are heartbreaking, “The Missing Kennedy” shows how her family’s relationship with her ultimately advanced Americans’ understanding of and compassion for those with disabilities. It proved to be a powerful catalyst.

The evidence for this can be seen in Eunice Kennedy Shriver’s founding of the Special Olympics and her son Anthony’s founding of Best Buddies International (which supports students with intellectual and developmental disabilities), among many other such organizations. And President Kennedy vigorously pushed federal legislation on behalf of those with intellectual disabilities, starting with the recommendations of his President’s Panel on Mental Retardation in 1962.

An interesting appendix details these and the other many ripples from Rosemary’s story. “The Missing Kennedy” shows her legacy to be far-reaching indeed as we continue to learn how to treat those “least among us,” the intellectually disabled, with compassion, respect, and dignity as did Sister Paulus and the nuns of St. Coletta’s, starting long ago.

***

Roberts is the author of two books about Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker and teaches journalism at the State University of New York at Albany.

PREVIOUS: Not much to love in ‘The Hateful Eight’

NEXT: ‘The Masked Saint’ tells tale of pastor, wrestler, vigilante

Share this story