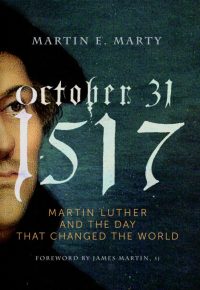

“October 31, 1517: Martin Luther and the Day That Changed the World”

“October 31, 1517: Martin Luther and the Day That Changed the World”

by Martin Marty.

Paraclete Press (Orleans, Massachusetts, 2016).

114 pp., $19.99.

It has been 500 years since Augustinian monk and theology professor Martin Luther set off the Protestant Reformation with his call for a debate on indulgences and other burning issues in the Catholic Church at the time. Prolific Lutheran writer Martin Marty centers his reflections on Luther’s 95 theses on Christ’s call to repentance, arguing that repentance formed the heart of Luther’s spiritual crisis.

What might make this book challenging for many readers is the author’s tracing of the history of Lutheran-Catholic rapprochement that led to a 1999 joint declaration on grace. While this topic is treated with sensitivity, it was the Catholic side that seemed to give more on the issue of grace as central to salvation.

The book at times addresses ecumenism as much as repentance, basing the first on the second. Present-day Western Christians have taken a close look at past theological clashes, some of which led to war. Yet Marty urges us to look to the present and future: “We know that the past is past. It does not exist. It cannot be changed. What can be changed is one’s attitude.” He bids that we ask ourselves how we today contribute to division within the church and to repent of this.

[hotblock]

Marty never advocates an easy ecumenism because he never advocates an easy repentance. He reminds readers, for instance, that many Lutherans and Catholics were not so supportive of the recent steps toward reconciliation. He examines the many outstanding issues, including Communion, noting how these touch each believer:

“Catholics and Lutherans in their homes, parishes, social action, seminaries and gatherings have the opportunity to newly treat practices and teachings that still separate them and prevent the unitive commands, promises, and practices from being further developed,” he writes. Ecumenism again mirrors Marty’s concept of repentance: It is ongoing and never really finished. It is a lifelong journey.

One way the author attends to current divisions, such as over the sacraments, is by showing where, in the diverse views, one can find a common root or a unified conclusion. This is the hard work of ecumenism, doing one’s theological and historical homework to find where the various traditions share certain things. Just as Catholics became more open to the Lutheran conception of grace, so Lutherans have seen the depth of Catholic sacramental theology: “Lutherans have come to recognize more than before what Catholics stress: that baptism makes one an organic member of a community, the community that is the body of Christ.” Each side deepens the understanding of the other.

Marty also finds commonality in the Eucharist, hinting that the real issue here has been a misunderstanding resulting from the simpler Lutheran concept of “in, with and under” compared to the much more philosophical Catholic transubstantiation. He sees Lutherans as having more problems with other Protestants, who have spiritualized the Eucharist, than with Catholics, though he does mention the Lutheran discomfort with eucharistic adoration.

[hotblock2]

Marty explains Lutheran-Catholic differences here in a clear, straightforward manner, highlighting both commonalities and differences. This honest approach surpasses any attempt at sugarcoating differences so that we can all be nice to each other and get along. Marty is not willing to give up the truth. Such ecumenism, though more difficult, will yield better results in the long run.

This means that while he mentions women’s ordination, which is a large hurdle to closer Lutheran-Catholic relationships, he leaves it as is. But one area of potential confusion here, as elsewhere in the book, is the question of which Lutheran denominations one is talking about, because many do not ordain women. The author tends to overlook such intricacies. Small books such as this come at the price of deeper analysis of the various issues. Perhaps this attests to the author’s humility, as he never attempts to prescribe the necessary treatment to every ecumenical ill.

Marty’s central message at the 500th anniversary of the start of the Protestant Reformation seems to be that it is not only a Protestant anniversary, but a Catholic one too. While Luther’s initial actions and Rome’s reactions led to deep crisis and sometimes violent divisions, Marty writes convincingly that the commemorations can actually bring Protestants and Catholics together. This is a surprising and grace-filled way of looking at the anniversary, perhaps one that is inspired by the Holy Spirit.

***

Also of interest: “All Things Made New: The Reformation and its Legacy” by Diarmaid MacCulloch. Oxford University Press (New York, 2016). 464 pp., $29.95.

***

Welter has degrees in history and theology, and teaches English in Taiwan.

PREVIOUS: A bravo performance but immoral end for ‘The Girl on the Train’

NEXT: Movie review: Queen of Katwe

Share this story