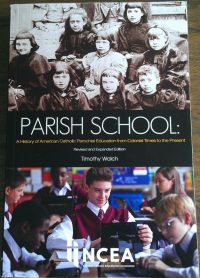

“Parish School: A History of American Catholic Parochial Education from Colonial Times to the Present

(Revised and Expanded Edition)”

by Timothy Walch,

267 pp.

(Available through the National Catholic Educational Association website: www.ncea.org for $23 plus shipping.)

Twenty years ago, historian Timothy Walch predicted that Catholic schools would survive into the 21st century and “continue to influence the contours of public education as well as prepare young Catholics for future leadership roles in the Church and in American society.”

Walch made that prediction to The Catholic Messenger, newspaper of the Diocese of Davenport, Iowa, in a Feb. 22, 1996, article about his new book, “Parish School: A History of American Catholic Parochial Education from Colonial Times to the Present.”

[hotblock]

In a revised and expanded edition of “Parish School” published this year, Walch, a member of St. Thomas More Parish in Coralville, Iowa, remains bullish about Catholic schools. He writes: “As long as there are parents and pastors interested in parochial education, these schools will survive. Even though American Catholic parochial education will never again attain the position of influence it had in the mid-20th century, parish schools will remain important education laboratories for some time to come.”

The National Catholic Educational Association issued the new edition of “Parish School” with good reason. Walch has written extensively about Catholic education and provides a rearview mirror perspective that ought to help the drivers of Catholic school education on the journey ahead. “For all the recent efforts to ensure Catholic education, we should not lose track of the traditions that sustained these schools in the past,” Walch observes. “Going forward, we need to remember our heritage.”

Walch does just that in a 267-page book that includes a 60-page guide to further reading and research.

“Parish School” is an effort, he says, to “trace the contours of American Catholic parochial education from their origins in the missionary and colonial eras and analyze the importance of these schools for successive generations of American Catholics.”

Among the themes he covers in the book are the survival of the Catholic faith in a hostile land; immigration, which led to explosive growth in Catholic schools; the parish school movement; and adaptability, community building and identity.

Equally valuable are the insights Walch provides about forces within and outside of the church which impacted the development of Catholic schools. He noted that the then-U.S. Office of Education wrote in a 1903 report that the system of Catholic free parochial schools was the most impressive religious fact in the country at that time. Walch observed that this achievement came at a high price: disjointed and uncoordinated, rapid growth of parochial schools — which in turn gave impetus to centralized, diocesan school supervision.

While Walch identifies sister-teachers as the single most important element in the establishment of Catholic education, he also chronicles the years-long struggle to ensure that they were adequately trained to teach. Their religious communities gave higher priority to the cultivation of the sisters’ religious vocation, he notes.

Walch writes admiringly about a priest educator, Father Thomas Shield, who persevered in establishing a Sisters College adjacent to the campus at The Catholic University of America in Washington to educate the sisters. But the true motivator for improvement in the quality of Catholic school teacher preparation was a state requirement for teachers to be certified.

[hotblock2]

Interspersed in “Parish School” are anecdotes about clergy and laypeople who left an imprint on Catholic schools. Walch writes about a young housewife, Mary Perkins Ryan, who in 1964 dared to ask a startling question in her book: “Are Catholic Schools the Answer?” She viewed Catholic schools as parochial in the pejorative sense and an obstacle to the Catholic mission of witnessing the presence of Christ. Walch says the book hit the Catholic education establishment like a ton of bricks. And it’s a question that continues to be asked today.

Walch, who also serves on The Catholic Messenger board of directors, is convinced the answer is a definitive “Yes.” He argues that Catholic schools are both a model for and an alternative to public education. They develop effective tools for reaching a broad cross section of students. One innovative approach that Walch identifies is the incorporation of business and marketing strategies to address parents’ demand for clarity of mission, accountability and a focus on core functions. Another example focuses on the use of technology to stimulate individualized education.

The book also addresses the various financial initiatives that Catholic schools across the country use to ensure that all students who want to attend a Catholic school have the ability to do so. School choice has become the mantra in many states, including Iowa.

At its essence, a Catholic school seeks to prepare leaders and Christian stewards for the community and for the future of the church, as the mission statement for the Catholic schools of the Davenport Diocese states. “Parish School” serves as a great resource in understanding the framework.

***

Arland-Fye is editor of The Catholic Messenger, newspaper of the Diocese of Davenport.

PREVIOUS: Spanish-language booklet outlines challenges to U.S. Hispanic ministry

NEXT: ‘The Edge of Seventeen’ goes over the edge of exploitation

Share this story