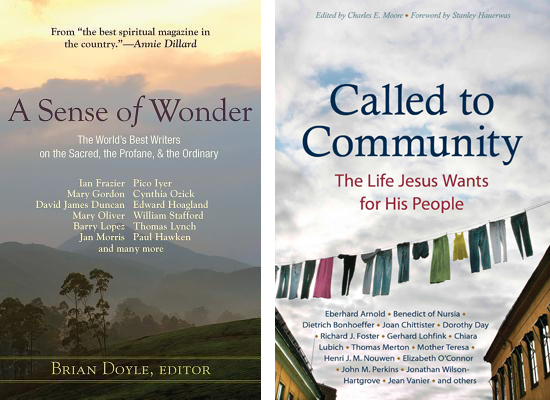

“A Sense of Wonder: The World’s Best Writers on the Sacred, the Profane & the Ordinary,”

edited by Brian Doyle.

(Orbis Books, Maryknoll, New York, 2016).

208 pp., $20.

“Called to Community: The Life Jesus Wants for His People,”

edited by Charles E. Moore.

(Plough Publishing House, Walden, New York, 2016).

354 pp., $18.

These two anthologies offer a splendid trove of insights about spirituality and Christian community.

“A Sense of Wonder: The World’s Best Writers on the Sacred, the Profane & the Ordinary” collects 37 essays and personal stories from Portland Magazine. This award-winning university magazine has featured the work of writers such as Mary Gordon, Mary Oliver, William Stafford and Pico Iyer, all included in this stunning collection.

Brian Doyle, editor of Portland Magazine, has gathered an impressive, wide-ranging assortment of pieces. His own contribution, “The Late Mister Bin Laden: A Note,” is an original reflection on the death of Osama bin Laden that laments the squandering of God-given gifts that his life represented.

[hotblock]

In one of the book’s most compelling selections, Oliver walks through a field and her poet’s eye recognizes that everything is “attached by its unbreakable cord to everything else.” She writes, “Teach the children. … Show them daisies and the pale hepatica. The lives of the blue sailors, mallow, sunbursts, the moccasin flowers. … Give them peppermint to put in their pockets as they go to school. Give them the fields and the woods and the possibility of the world salvaged from the lords of profit. Stand them in the stream, head them upstream, rejoice as they learn to love this green space they live in, its sticks and leaves and then the silent, beautiful blossoms. Attention is the beginning of devotion.”

Novelist Iyer writes eloquently about the many chapels that have provided him peaceful refuge, from St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York to modern airport chapels to a jungle chapel in Sri Lanka during its civil war. “So much of our time is spent running from ourselves, or hiding from the world; a chapel brings us back to the source, in ourselves and in the larger sense of self — as if there were a difference,” he observes. And, “If your silence is deep enough, bells toll all the way through it.”

When Gordon reminisces about her first Communion, some five decades ago, she gives us a moving meditation on what, for her, endures: “The taste for the invisible … my highest self, the truest one.”

Stafford, the late poet laureate of both Oregon and the United States, is represented by “Every War Has Two Losers,” which underscores the insanity of war. And Thomas Lynch, author of such books as “The Undertaking” and “Booking Passage,” offers profound reflections on the human condition of “hate and love and possibility” in an essay titled “One of a Kind and All the Same.” He ponders the meaning of the Human Genome Project’s revelation that “Mother Teresa and Adolf Hitler have much in common,” while “George Custer and Catherine of Siena, Mandela and Milosevic are genetically much the same.”

In “When I Was Blind,” Edward Hoagland shows how his “blindness was full of second sight,” revealing the rich alternate world that he could now see. “When you are blind,” he notes, “you can hear people smile — there’s a soft click when their lips part.”

One of the most charming and insightful essays is Holy Cross Father Charles Gordon’s “Why I am a Priest.” He explores, with both humor and gravity, the many reasons that led him to his vocation.

[hotblock2]

All in all, “A Sense of Wonder” is a stirring and heartfelt book that inspires the reader to ponder both the everyday and the eternal.

“Called to Community: The Life Jesus Wants for His People” gathers 52 different essays on the challenges of living in Christian community. Most of the authors have actually walked the talk, living in intentional community and thereby gaining a deep understanding of its challenges. Works by St. Benedict of Nursia, Lutheran theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Dorothy Day, Trappist Father Thomas Merton, Father Henri J. M. Nouwen, Mother Teresa and Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, among many others, are included here.

The book is divided into four well-integrated sections. First, “A Call to Community” deals with the foundational ideas of Christian community. Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-1881), who inspired the Christian communitarianism of Day’s Catholic Worker movement, is fittingly represented here by a passage from his novel “The Brothers Karamazov,” in which he decries “terrible individualism.”

Also in this section, Bonhoeffer’s (1906-1945) “A Visible Reality” discusses some of the key New Testament passages that underscore the importance for Christians of living in community.

“Forming Community” (Part II) and “Life in Community” (Part III) offer many practical suggestions about how to establish and maintain community. Here, Jean Vanier (born 1928), the French spiritual writer and founder of L’Arche community, differentiates the worthy goal of “communion” from its lesser counterparts of “collaboration” and “cooperation.”

“When people collaborate,” Vanier writes, “they work together toward the same end, in sports, in the navy, or in a commercial venture. …They are brought together by a common goal, but there is not necessarily communion between them. They are not personally vulnerable one to another.”

But, Vanier continues, “When there is communion between people, they sometimes work together, but what matters to them is not that they succeed in achieving some target, but simply that they are together, that they find their joy in one another and care for one another.”

In an essay titled “Irritations,” Father Anthony de Mello (1931-1987), the Indian Jesuit priest, wisely advises: “Every time you find yourself irritated or angry with someone, the one to look at is not that person but yourself. The question to ask is not, ‘What’s wrong with this person?’ but ‘What does this irritation tell me about myself?'” (In a posthumous notification concerning his writings, the Vatican Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith June 24, 1998, said some the priest’s views were “incompatible with the Catholic faith and can cause grave harm.” It particularly cited those views presenting God as an impersonal cosmic reality, organized religion as an obstacle to self-awareness and Jesus as one master among many.)

Mother Teresa, canonized this year as St. Teresa of Kolkata (1910-1997), founder of the Missionaries of Charity, offers insights about our “Deeds”: “If you are working in the kitchen, do not think it does not require brains. Do not think that sitting, standing, coming, and going, that everything you do, is not important to God.” And, she said, “if we really want peace for the world, let us start by loving one another within our families. … In order for love to be genuine, it has to be above all a love for our neighbor.”

In Part IV, “Beyond the Community,” the American clergyman Eugene H. Peterson (born 1932) discusses the problem of sectarianism in Christian community, while Day (1897-1980) contributes the final essay that encourages us to practice the spiritual works of mercy.

The range of authors and faiths represented is commendable. It includes Catholic, mainline Protestant, Mennonite, Quaker and other perspectives, both American and international, lay and clerical.

This is a stellar contribution to our understanding of the whys and wherefores of Christian community. The 52 selections seem perfect for a year of weekly group study and the detailed discussion guide in the appendix is particularly useful for this purpose. “Called to Community: The Life Jesus Wants for His People” is a thoughtfully compiled and well edited guide to the subject.

***

Roberts is the author of two books on Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker and teaches journalism at the State University of New York at Albany.

PREVIOUS: ‘Miss Sloane’ no paragon of virtue while fighting for convictions

NEXT: With ‘Rogue One: A Star Wars Story’ the Force will be with us, always

Share this story