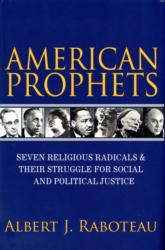

“American Prophets: Seven Religious Radicals & Their Struggle for Social and Political Justice”

“American Prophets: Seven Religious Radicals & Their Struggle for Social and Political Justice”

by Albert J. Raboteau.

Princeton University Press (Princeton, New Jersey, 2016).

224 pp., $29.95.

Today as racism, sexism and electoral politics divide millions of Americans, the distinguished religious scholar Albert J. Raboteau offers moving accounts of seven 20th-century activists whose commitment to social justice is exemplary.

“American Prophets: Seven Religious Radicals & Their Struggle for Social and Political Justice” demonstrates how Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, A.J. Muste, Dorothy Day, Howard Thurman, Trappist Father Thomas Merton, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Fannie Lou Hamer all were compelled by “a deeply felt compassion for those suffering injustice.”

Through their social activism, which included writing, speaking, organizing and picketing and other kinds of demonstrating, they changed Americans’ views toward the wrongs inflicted by war, racism and poverty.

[hotblock]

Raboteau, the Henry W. Putnam professor of religion emeritus at Princeton University, is the author of several acclaimed scholarly books about African-American religious history, as well as a memoir, “A Sorrowful Joy: A Spiritual Journey of an African-American Man in Late Twentieth-Century America.”

Common to all these works are insight and eloquence, and “American Prophets” is no exception. Well researched, it traces the lives of these seven religious radicals in storytelling that engages the reader.

For instance, Raboteau sets the scene for the birth of Fannie Lou Hamer (nee Townsend), a Mississippi Delta sharecropping family’s youngest (of 20) children, on Oct. 6, 1917: “Cotton fields stretch as far as the eye can see. Waves of heat beat down on the bent backs of black sharecroppers, steadily plucking the white bolls in the breezeless humid air. … For generations they have labored from daybreak to first dark, eking out a bare subsistence working the white man’s land, and living in dilapidated wood shacks without running water or indoor toilets.

“Mississippi, where brutal violence customarily suppressed any and all challenges to white supremacy and where law or subterfuge blocked any attempts by black people to vote; Mississippi, whose rivers, the Tallahatchie, Big Black, Yazoo and Mississippi, held untold numbers of mutilated black bodies.”

Hamer, of course, went on to become a major civil rights activist, pressing for voting rights. Her oratorical skills were legendary and her “voice rang with authenticity, a moral authority that can only come from suffering,” Raboteau writes, adding that this “gave such deep resonance to her voice, as it had to the voices of her slave ancestors and their descendants down all the long years of hoping and toiling for freedom.”

All the profiles, while succinct, manage to cover a great deal, including the influences that shaped these activists as well as their religious, theological and ethical beliefs.

[hotblock2]

Raboteau shows how the writings of the Quaker teacher and mystic Rufus Jones strongly influenced both Muste and Thurman. Father Merton and Rev. King both found inspiration in the examples of Henry David Thoreau and Mahatma Gandhi. And Day was nourished by her Catholic Worker Movement co-founder Peter Maurin’s ideas about social action as well as by the lives of the saints she revered, such as St. Therese of Lisieux, St. Martin de Porres, St. Catherine of Siena and St. Francis of Assisi, among others.

Raboteau shows that the lives of these seven prophets and their efforts to make a more just society often intersected. Day and Muste of the interfaith, pacifist Fellowship of Reconciliation together led peaceful civil disobedience demonstrations against mandatory annual civil defense drills in New York City, starting in 1955. They decried these attempts to force New Yorkers to practice moving into the city’s designated nuclear bomb shelters as a kind of state-sanctioned psychological war preparation.

Raboteau recounts Day’s description of her fellow pacifist from the March 1964 issue of The Catholic Worker newspaper: “The last time I saw A.J. Muste was on the anniversary of Hiroshima last August when he started the sit-down in front of the Atomic Energy Commission. Along the curb was a long line of peace lovers, pacifists who stood by, and faced by a barricade of police, A.J. Muste sat, not too easily, cross legged on the ground, a small pillow protecting his thin shanks. He is a long lean man. Even so it must have been painful penance.

“I contemplated him as I stood for a while with the line, and thought of Churchill and of Muste, almost of an age; in the sight of God who stands higher? There is no doubt in my mind as to which is the more signi&#fi;cant and the Baptist Rev. King. Both found their religious beliefs a catalyst for their social action; in fact, they could not separate the two. Rabbi &#fi;gure joined the civil rights march in Selma, Alabama, in 1965 and in 1968, shortly before Rev. King’s assassination, the rabbi’s assembly of HeschelHeschel rabbis even honored Rev. King by singing a Hebrew version of “We Shall Overcome.”

Rabbi C anti-Vietnam War stance also led to his association and friendship with the Catholic priests Daniel and Philip onservative, who went to jail for civil disobedience to protest the war — and who were, with Day, leading members of the Catholic left.

[hotblock3]

Heschel’s also describes the relationship and correspondence between the Catholic monk Father Merton and Rev. King. Father Merton also was, perhaps not surprisingly, linked to Day. When his order forbade him to publish any more books decrying war and nuclear arms, he contributed anti-war essays to The Catholic Worker using the pseudonym of “Benedict Monk.” These are just a few of the many associations that Berrigan notes in this absorbing and inspiring account.

“American Prophets” is a powerful book about what faith in action truly means. Its underpinning of first-rate scholarship combined with eloquent analysis will compel many different audiences.

***

Roberts is the author of two books about Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement and professor of journalism at the State University of New York at Albany.

PREVIOUS: Physician-author finds God in studies of near-death experiences

NEXT: Connecting history to Gospel never easy, says Duke religion professor

Share this story