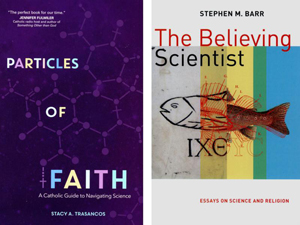

“Particles of Faith: A Catholic Guide to Navigating Science”

“Particles of Faith: A Catholic Guide to Navigating Science”

by Stacy A. Trasancos.

Ave Maria Press (Notre Dame, Indiana, 2016).

178 pp., $15.95.

“The Believing Scientist: Essays on Science and Religion”

by Stephen M. Barr.

Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing (Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2016).

226 pp., $25.

Few areas of thought today are as exciting and as important as the conversation between religion and science. Unfortunately, these two books don’t contribute that significantly to this dialogue. Both authors, with strong backgrounds in science and far weaker backgrounds when it comes to theology, disappoint the reader in different ways.

Stacy Trasancos, a chemist and a Catholic, teaches online from home while she helps raise and educate her children, and she talks early in her book about the excitement of seeing the connections between science and faith and does so well.

[hotblock]

However, besides Pope Francis’ encyclical “Lumen Fidei” (“The Light of Faith”), many of the theological sources she uses are pre-Second Vatican Council, such as St. Thomas Aquinas and the fathers of the church, helpful in the tradition but not as useful here as the many contemporary voices on this topic. Authors such as Father Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Franciscan Sister Ilia Delio, John F. Haught, Father Thomas Berry, Father Diarmuid O’Murchu and Judy Cannato merit not a mention here at all.

Trasancos is trying to address the right issues here. For example, she observes that “science can be the very venue through which we reach out into the world and shine our faith to illuminate the path to truth.” And she reminds us that “faith and science are two different manifestations of the same reality. When they seem to have conflicting conclusions, it is because our knowledge is not complete.”

There also are occasional stories from her experience as a mom; when her son heard her say that everything was atoms, he wanted to know if he was eating atoms and was told he was. “He put the idea of ‘science in the light of faith’ into words during our blessing: ‘Bless us, O Lord, and these thy atoms.’ Leave it to a child.”

At times her questions as well as her answers fall short. Examples of her questions that seem to be the wrong ones include: “Is the Atomic World the Real World?” “Does Quantum Mechanics Explain Free Will?” and “Did We Evolve from Atoms?” Her discussion of Adam and Eve and evolution seems to be woefully lacking in an understanding of the historical-critical method of interpreting Scripture, first encouraged by Pope Pius XII, which might see the Genesis account as true in another sense than scientifically.

This is a worthwhile effort, but unfortunately she is hindered here in her treatment by a limited and overly dogmatic theology, which changes the whole conversation.

Stephen Barr is a professor of theoretical particle physics at the University of Delaware and brings a highly academic perspective to the questions of science and religion. (It isn’t completely clear what his credentials are when it comes to theology.)

He, too, sets the perspective well for the reader: “It was in the heavens that the orderliness of nature was most evident to ancient man. It was this celestial order, perhaps, that first inspired in him feelings of religious awe. And it was the study of this order that gave birth to modern science in the 17th century. It is not altogether accidental, then, that it was an argument over the motions of the heavenly bodies that occasioned the fateful collision between science and religious authority that will forever be evoked by the name of Galileo.” (He goes on to talk about that controversy as being between two naturalistic theories of astronomy, not as supernatural.)

[hotblock2]

He also describes the role of the scientist in an interesting light: “So we see in science something akin to religious faith. The scientist has confidence in the intelligibility of the world. He has questions about nature. And he expects — no, more than expects, he is absolutely convinced — that these questions have intelligible answers. The fact that he must seek those answers proves that they are not in sight. The fact that he continues to seek them in spite of all the difficulties testifies to his unconquerable conviction that those answers, although not presently in sight, do in fact exist. Truly, the scientist too walks by faith and not by sight.”

The bulk of Barr’s book, as indicated by his subtitle, are essays, largely book reviews or comments on blogs, as well as an occasional lecture, which have limited usefulness to the reader unfamiliar with the specifics of what he is referring to.

One hopes for more helpful books than these in the conversation between faith and science soon.

***

Finley is the author of several books on practical spirituality, including “The Liturgy of Motherhood: Moments of Grace” and “Savoring God: Praying With All Our Senses,” and has just finished teaching in the religious studies department at Gonzaga University.

PREVIOUS: ‘Hidden Figures,’ ‘Hacksaw Ridge’ among Christopher Award winners

NEXT: ‘The Blackcoat’s Daughter’: Another psych horror film cloaked in possession

Share this story