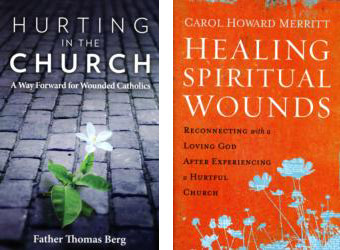

“Hurting in the Church: A Way Forward for Wounded Catholics”

by Father Thomas Berg. Our Sunday Visitor (Huntington, Indiana, 2017). 208 pp., $15.95.

“Healing Spiritual Wounds: Reconnecting With a Loving God After Experiencing a Hurtful Church”

by Carol Howard Merritt. HarperOne (New York, 2017). 232 pp., $25.95.

In the opening paragraph of “Hurting in the Church,” Father Thomas Berg writes, “I am writing for Catholics who, somewhere along life’s journey, have had a painful experience in the church.”

In other words, Father Berg’s readership could include almost any Catholic who has belonged to a parish, attended a Catholic school, had dealings with clergy and religious, or worked for a Catholic institution. That hurt can take multiple forms from the most egregious, e.g., from the sexual abuse of children by clergy and the subsequent indifference of church officials when the victims reported it to them to those subjected to clericalism.

[hotblock]

A priest of the Archdiocese of New York and professor of moral theology at St. Joseph Seminary, Father Berg is a former member of the Legionaries of Christ — a religious community that had been infected with scandal due to the illicit behavior, including the sexual abuse of seminarians, of its priest-founder, Father Marcial Maciel Degollado, who was held in high esteem by St. John Paul II.

An Vatican investigation into allegations against Father Maciel began in early 2005 under the pope but was not concluded until after his death in April 2005. In 2006 the Vatican ordered the priest to no longer publicly perform his priestly functions. Father Maciel’s behavior had a direct and indirect impact upon the order’s members and rendered the order spiritually and emotionally dysfunctional.

After telling his story of hurt due to what occurred in the Legionaries, Father Berg uses the remaining chapters to share stories of others who have been hurt, but also to provide a way — hope, really — for those seeking healing from hurts caused by the church.

If there is such a thing as a pastoral approach to writing, Father Berg employs it. In a chapter titled “A Heart-to-Heart About Catholic Priests,” he speaks in an honest but loving way about priests and to priests about prayer, relationships, joy, loneliness, backbiting and other facets of their vocation.

In a chapter titled “Who Am I to Judge?” Father Berg makes it clear that he agrees with the church’s teachings regarding contraception, cohabitation, divorce and remarriage, and homosexuality. Then he adds, “But I also believe it’s essential to listen to those who disagree. And I must admit that I’ve not always done a good job at that.”

Writing at length about the hurt the church has caused homosexual individuals, the pastoral tone of his work is evident as he writes about judging a person and a person’s behavior. With that he asks, “But does my unwillingness to validate their lifestyle choices mean we can’t love each other anyway? Does that mean that the love I could have for them is a farce and a contradiction in terms?”

Whatever the wound, the priest’s steady, guiding, loving and personal process will help the reader deal with the hurt — and the church that caused it. Written by someone who hadn’t experienced “church wound,” the content of “Hurting in the Church” might read as preachy, hollow and detached from reality. But Father Berg experienced the hurt deeply, and took the steps needed for healing. What he shares is practical and has the potential to help wounded readers heal, too.

Carol Howard Merritt’s story of hurts and her pursuit of healing them that, as she writes “begins and ends with God,” include life with an abusive father to a spiritually and emotionally abusive seminary experience.

She writes with an intensity that confronting the pain and committing to healing requires. It is not enough for the hurting person to merely read Merritt’s work; the reader, to get full benefit from what she writes, must be willing to engage in the exercises she provides at the end of each chapter.

While they might sound easy, e.g., “Claiming God’s Love” in a chapter on redeeming the broken self, and “Revealing Your Fears” in a chapter about redeeming hope, the exercises she assigns require readers to dig deeply into their lives — and their pain.

A Presbyterian minister, Merritt is clear in taking “the church” to task, i.e., particularly, but not limited to, fundamentalist sects, for the pain they have caused members by their words and actions — or lack thereof. Also among those she criticizes is St. Augustine for his views on women, which she terms “bitter delusions.”

Early in the book, Merritt notes she is writing “for those who feel the deep wounds caused by religion and who, like me, want to heal from them.”

Those seeking that healing will find “Healing Spiritual Wounds” a valuable resource in doing so. Those who have not yet come to grips with their religion-caused hurt can start that process here.

***

Olszewski is editor of The Catholic Virginian, newspaper of the Diocese of Richmond, Virginia, and has written for and edited Catholic publications for more than 40 years.

PREVIOUS: Wilderness trek takes the usual route in ‘The Mountain Between Us’

NEXT: ‘My Little Pony: The Movie’ is as sweet as it comes

If Father Berg doesn’t recognize that the Church’s insistence on its traditional teachings on the morality of sexual behaviour is abusive in itself, I wouldn’t trust him.