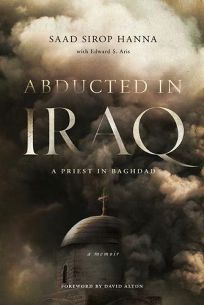

“Abducted in Iraq: A Priest in Baghdad”

“Abducted in Iraq: A Priest in Baghdad”

by Saad Sirop Hanna, with Edward S. Aris.

University of Notre Dame Press (Notre Dame, Indiana, 2017).

169 pp., $25.

“You don’t hate us, do you?” One of Father Sirop Hanna’s captors asked that question as the young Chaldean Catholic priest’s month-long captivity in Iraq came to an end.

Today Father Hanna is an auxiliary bishop of Baghdad. He was kidnapped Aug. 15, 2006, after Islamic extremists surrounded his car on a southern Baghdad street.

His captor’s question came after a seemingly endless series of days during which he was transported from one unknown place to another and another while blindfolded in a vehicle’s trunk, endured countless violent beatings and received all too little by way of food or drink.

[hotblock]

“No, I don’t hate any person,” he answered his captor. “My faith asks this of me, to love all people. Even those who harm me. I don’t always accept the things they do, but I don’t hate them.”

“Abducted in Iraq” was written a decade after his captivity. The book tells the painful, day-by-day story of those days and of his survival — his physical survival, to be sure, but the survival too, indeed the flourishing, of his faith under the most senselessly hurtful circumstances.

He recalls how he “endeavored to overcome, to move past” his captivity’s awfulness and do what he always had done by turning “to God for answers.” But “to pray is to listen,” he writes. So he “asked of God: ‘What do you want from me? What am I to do?'”

In the end he tells of becoming “reborn into (his) purpose: to tell others that faith need not wilt in the face of difficulties but can blossom, offering greater clarity, that a belief in the love of God compels us to see the love in one another.”

Love, he concludes, “must be the driving force for all people, to ‘love your enemy,’ to look beyond the threats of the here and now, to look beyond ethnicity, creed, culture or religion and to connect on a level of shared humanity.”

His captors’ purpose, it appears, was complex and shifting. They sought ransom, but also sought vigorously to convert their captive priest to Islam, viewed by them as the true religion. They promised him a future as a teacher.

Were they surprised to learn he was “important?” Not only his patriarch but Pope Benedict XVI as well appealed for his release.

“Ask the people about the priest,” then-Father Hanna urged his captors. “Don’t ask the Christians, go ask the Muslims about the priest of this area, and see what they tell you.”

His refusal to convert was met with torture. “Back I fell, my head buzzing from the impact, and then came another and another and another. The wooden stick whipping through the air as they struck me,” he reports.

“I am not a soldier, and you and I, we are not at war,” Father Hanna said to a leader among his captors regarding his refusal to convert. “I am a man who helps people. But … I will not change my mind, and I have nothing to fear from any of you.”

[hotblock2]

A continual flow of grave threats and painful moments mark this book’s pages. They are marked, too, by the author’s refusal to allow his captivity to justify hatred toward Muslims.

The frequent presence of his Muslim guard, Abu Hamid, highlights this subtheme. Hamid’s kindnesses toward him shine like a light in darkness; something close to friendship is forged.

After Father Hanna attempts a daring but doomed escape by running toward and then swimming across the Tigris River, this friendship comes into clearest view. Realizing that Hamid will be blamed for the escape, Father Hanna, suffering yet another beating, exclaims: “You want to kill me? … Do it. … But if you kill that guard, then you kill an innocent man. One of your own.”

“Abducted in Iraq” is a gripping account of profound faith, authentic courage and hope against all odds. Not surprisingly, the priest’s cruel confinement led him to ponder life’s ultimate questions, like love’s meaning, God’s presence and action, and goodness itself.

“Goodness,” he writes, “is an invisible substance. You cannot really tell its strength until it’s tested, until enough of life is piled on it and you can hear it creak with the weight of … the temptation to forego what can be done in exchange for the ease of not doing.”

Possibly, he speculates, true goodness only finds “its measure” under “the direst of circumstances.”

***

Gibson was the founding editor of Origins, Catholic News Service’s documentary service. He retired in 2007 after holding that post for 36 years.

PREVIOUS: New Testament prof sorts out plausible, implausible in new ‘Paul’ movie

NEXT: ‘A Wrinkle in Time’ seeks virtue in the secular and magical

Share this story