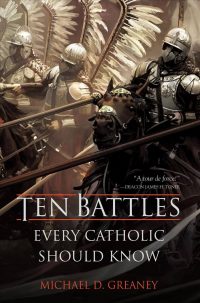

“Ten Battles Every Catholic Should Know”

“Ten Battles Every Catholic Should Know”

by Michael D. Greaney.

Tan Books (Charlotte, North Carolina, 2018).

266 pp., $27.95.

Michael Greaney ties political, social and psychological factors into his riveting history of Turkish military incursions into Europe. After opening with the 11th-century’s Battle of Manzikert in Anatolia, the author spends the rest of the book examining military clashes in eastern Europe and the Mediterranean during the Ottoman’s zenith from 1462 to 1621.

The author’s focus on the individuals who played pivotal roles in these confrontations — emperors, sultans, popes, commanders and knights — makes this history vivid and memorable. Military commanders could often make or break a battle or siege.

[hotblock]

For instance, Knights Hospitaller Grand Master Jean de La Valette coordinated the defense of the Maltese outpost Castle Sant’Elmo in 1565 to slow down the Turks’ advances on more important military installations. The author captures both the character of this man and the morale of soldiers:

“Late one night, a delegation from Sant’Elmo slipped across the Grand Harbor to Sant’Angelo. Realizing that their situation was hopeless, a number of the younger knights requested permission to abandon their station. La Valette shamed them into going back by declaring that he would himself go with a picked band and take up their posts.”

For the Battle of Lepanto, which saved Western Europe, another such commander is depicted:

“Although he was 75 years old, Sebastiano Veniero, stationed to the left of Don Juan, took an active part in the battle. … Too feeble to crank the (crossbow’s) windlass himself, a sailor was detailed to assist him. Veniero could still discharge his weapon, however, and calmly concentrated his bolts on the Turkish sharpshooters who had been assigned to bring him down as opposing admiral. Picking them off one by one, he exclaimed that he would count himself fortunate if his days should end in such a battle, God willing.”

Every engagement portrayed includes such details, making this book difficult to put down.

Along with these individuals, the author emphasizes the importance of cannon and harquebus (early rifle) fire, and the tragedy of the Turkish use of slave labor as cannon fodder and laborers digging tunnels under walls. These slaves, often Hungarian or Croatian, were worked to death or shot dead by defenders.

Highlighted military strategy includes battle formations, military equipment, siege warfare and soldiers’ conditions, including the famous Janissaries. Another form of slavery, Janissaries were often kidnapped as boys from Eastern Europe. As the author points out repeatedly, the Ottomans plundered Eastern Europe for slaves, tribute money and military provisions.

Yet Europe’s divisions, still passionate and festering from the Reformation, and French foreign policy, working with the Ottomans against Central Europe’s Habsburg rulers, meant that Croats, Hungarians or Romanians usually fought alone. As with any empire, the Turks would play the powerful in occupied lands off against each other. The author therefore adds greatly to the discussion by providing political background to the military encounters.

[tower]

For example, John Sigismund Zapolya turned to Turkish support after a failed attempt at being elected emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1566 on their Hungarian campaign the Ottomans “thus attempted to portray themselves as liberators and champions of the rightful heir to the Holy Roman Empire.”

This particular episode gives readers a taste of how violent and personal politics were, exemplified by the Croatian-Hungarian nobleman Count Zrinyi, who “staged a daring raid on a Turkish contingent” led by one of the sultan’s favorite commanders. The commander and his son were killed. The sultan, previously planning another siege of Vienna, sought revenge by attacking Count Zrinyi at his fortress, Szigetvar. Again, the author’s character profiles bring this violence to life.

On the downside, extra, marginally related information at the end of chapters creates a serious break in the flow. The Battle of Lepanto is, strangely, concluded with a discussion of the history of the rosary. Going into some detail on how anxious East European Christians prayed the rosary in the days leading up to that battle would have fit, but discussion of the rosary’s medieval origins or 20th-century rosary practices, however important, could have been included separately in an appendix.

Despite this important shortcoming, “Ten Battles Every Catholic Should Know” offers a timely, highly relevant alternative to the politically correct rendition of European and Christian history by depicting our Catholic ancestors’ great heroism.

***

Welter has degrees in history and theology and teaches English in Taiwan.

PREVIOUS: In ‘Alpha,’ a boy and his dog bond in Ice Age adventure

NEXT: ‘Mile 22’ is not worth the trip

Share this story