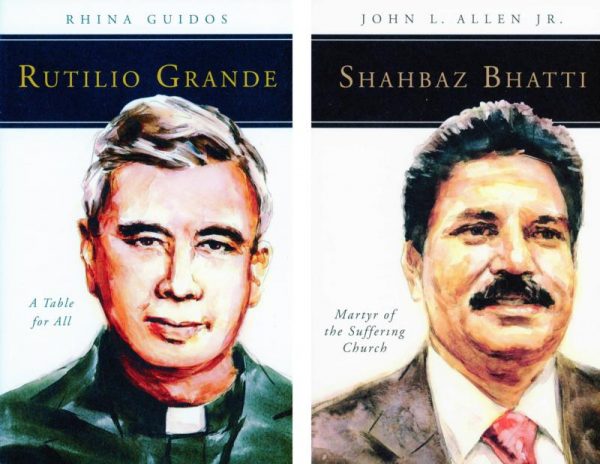

“Rutilio Grande: A Table for All”

by Rhina Guidos.

Liturgical Press (Collegeville, Minnesota, 2018).

121 pp., $14.95.

“Shahbaz Bhatti: Martyr of the Suffering Church”

by John L. Allen Jr.

Liturgical Press (Collegeville, Minnesota, 2018).

130 pp., $14.95.

The newest entries in Liturgical Press’ People of God series, these books offer accessible, edifying biographies that are the hallmark of the excellent series. In engaging and incisive narratives they tell the personal and public stories of two contemporary martyrs who have been proposed for canonization.

Father Rutilio Grande (1928-1977) was a Salvadoran Jesuit who was brutally murdered during the civil war. His death had a profound impact in the radicalization of his close friend, St. Oscar Romero (canonized Oct. 14, 2018).

[hotblock]

Shahbaz Bhatti (1968-2011) was a Pakistani layman, politician and human rights worker who founded the All Pakistan Minorities Alliance and was assassinated because of his work against blasphemy laws.

Father Grande and Bhatti are well served by their biographers, both experienced journalists who provide context for these compelling narratives.

Guidos is less detailed than Allen and her writing tends to the hagiographic rather than analytical. She has an evident affection and admiration for Rutilio Grande and narrates his story with empathy for his difficult childhood and psychological frailty and profound respect for the process through which he became a “martyr of rural evangelization.”

Father Grande was born in 1928 in the small town of El Paisnal, the youngest of six sons in a stable, modest family. Shortly after his birth, his parents divorced, their small business failed and his older brothers became tenant farmers. Raised by his paternal grandmother, from whom he absorbed “her vast religious knowledge and fervor,” his “identity was shaped by the life, language and reality of the rural world around him.”

His religious formation took him far from those roots. After seminary education, he entered the Jesuits, studied in Ecuador, Panama, Spain and Belgium, and returned to El Salvador with a commitment to the church of the Second Vatican Council.

He imparted that vision to the young seminarians he taught. He “was giving life to the teachings of Vatican II and Medellin in the places where they were meant to have life birthed into them: among the poor and marginalized communities, which were at that time largely found in El Salvador’s rural areas.”

[tower]

In January 1977, a Colombian priest who worked with rural communities was kidnapped, beaten and expelled.

“The peasants had been alarmed about the assault on their pastor and asked what the church planned to do about the incident.” The hierarchy did not respond, but Father Grande became increasingly eloquent in his denunciation of injustice. Three months later he was viciously murdered and, following his death, there was a rampant increase of violence in an area that was “once full of the vigorous religious life of the Catholic peasants.”

John Allen’s richly textured study of the life of Bhatti is explored in the context of the suffering of persecuted Christians. “The vast scale of Christian martyrdom in our time, and its truly global character, still has not excited anything like the public outrage and political mobilization the situation warrants.”

Bhatti was born and raised in a Catholic village in Pakistan’s Punjab region, in a “relatively high-status, middle-class family.” From his youth he combined piety and prayer with activism. In 1982, just 14, “he led a protest against a proposal to require Christians in Pakistan to carry special identity cards” and as a university student in Lahore he created an organization of Christian students “to unite them and defend their rights.”

Another time, at great danger to himself, he helped rescue a family of flood victims in Punjab. Bhatti admitted to fear, but “I defeated the fear of danger with the power of the Holy Spirit, with God’s blessing.”

Allen notes that Bhatti “brought the same conviction in the triumph of spiritual power over human fear to the later stages of his career, including his campaigns against Pakistan’s blasphemy laws and in favor of minority rights.”

Allen offers a succinct history of Christianity in Pakistan, the heavy burden of the blasphemy laws and a depressing litany of acts of anti-Christian violence. This was the environment in 2002 when Bhatti convened the All-Pakistan Minorities Alliance, “the cause that would become his life’s work … propel him into public office and also make him public enemy No. 1 for Pakistan’s radical Islamic factions.”

Allen’s compelling narrative of the mounting danger that Bhatti faced from Islamic extremists exactly mirrors Guidos’ description of the violence that shadowed Father Grande in the Catholic country of El Salvador.

Both men knew death was the possible outcome of their work and they faced this prospect with courage and fortitude. Whether or not they are eventually canonized, these biographies allow us to learn about, and from, two contemporary men who lived, and died, with heroism, service and radiant faith.

***

Linner, a freelance writer and reviewer, has a master’s degree in theology from Weston Jesuit School of Theology.

PREVIOUS: Beauty is skin deep in ‘The Nutcracker and the Four Realms’

NEXT: ‘Nobody’s Fool’ mocks divine gift of human sexuality

Share this story