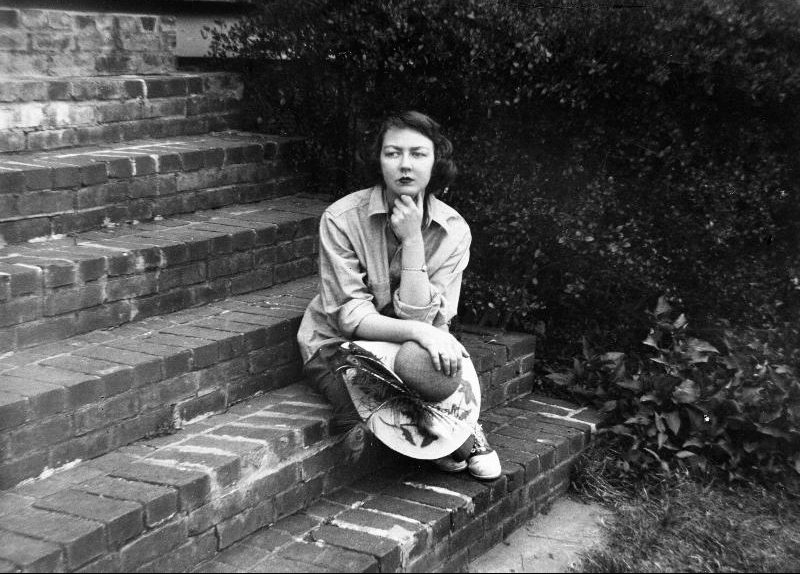

Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor is seen in a Sept. 22, 1959, photo, sitting on the steps of her home in Milledgeville, Ga. Elizabeth Coffman, an associate professor of film and digital media at Loyola University Chicago, co-directed the 2019 documentary “Flannery” with Jesuit Father Mark Bosco, vice president for mission and ministry at Georgetown University in Washington. The film, about the life and writings of O’Connor, recently won the Library of Congress Lavine/Ken Burns Prize for Film. (CNS photo/Floyd Jillson/Atlanta Journal-Constition, via AP, courtesy “Flannery”)

WASHINGTON (CNS) — It’s not every day that a documentary film director gets a congratulatory phone call from legendary filmmaker Ken Burns.

But that’s what happened in mid-October for Elizabeth Coffman, an associate professor of film and digital media at Loyola University Chicago, who got a call from a New Hampshire area code while she was teaching class.

She texted that she was teaching and asked if she could call back later.

[hotblock]

Sure enough, Burns, the award-winning documentarian, wanted to congratulate Coffman and Jesuit Father Mark Bosco, vice president for mission and ministry at Georgetown University, for winning the Library of Congress Lavine/Ken Burns Prize for Film for their 2019 film “Flannery” — about the life and writings of Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor.

Coffman and Father Bosco, former associate professor of English and theology at Loyola, co-directed the film that won the first annual prize of its kind and its accompanying $200,000 finishing grant.

The two received the award Oct. 17 at a Library of Congress gala in Washington and in the days since they have been talking a lot about the movie and attending film festivals with it.

Father Bosco said he has joked with fellow Jesuits that if O’Connor is ever up for canonization, the documentary’s award would count as her “first work of miraculous grace” because it has moved conversations about the writer to an entirely new level.

To date, the film has been shown primarily on college campuses, but it has been getting a broader audience starting with its world premiere Oct. 18 at the Hot Springs Documentary Film Festival in Arkansas. Days later, it was featured at the New Orleans Film Festival and on Oct. 27 it will be shown at the Austin Film Festival in Texas.

[tower]

The 96-minute film tells O’Connor’s story from interviews with contemporary writers and artists influenced by her such as actor Tommy Lee Jones and Alice Walker, author of “The Color Purple,” as well as motion graphic animations of pieces of her work and archival footage of an interview with the Georgia author.

O’Connor wrote two novels and 32 short stories known not only for their portrayals of the South but for their dark and sometimes comic imagery that revealed the human condition, warts and all, but also wove together Catholic themes of grace and redemption.

The “Flannery” screenings, with discussions afterward with one or both of the directors, have prompted animated discussions, reinforcing the directors’ views that the Southern Gothic writer, who died in 1964 at age 39 from Lupus complications, still has something to say for the current time.

“People respond with passion,” Coffman told Catholic News Service Oct. 22 from New Orleans, in between screenings.

“Really, a lot of people in the crowd in New Orleans were asking these detailed scholarly questions,” she said, adding that she jokingly asked some of the people in the audience if they were Ph.D. graduate students.

Coffman described the moviegoers as part of a “Flannery fan club” and said those who feel strongly about O’Connor like nothing more than to discuss her faith or her views on sexism and race.

If the film touches a nerve on these issues, it could be because they were the main things the directors wanted to convey. Father Bosco, an O’Connor expert, said he wanted the movie to give equal time to the writer’s Catholic faith, her white privilege and her sense of being a Southern person and someone with a disability.

The film took eight years to complete, mainly because as Father Bosco put it, he and Coffman both had day jobs.

The initial idea stemmed from a collection of archival interviews about O’Connor that the Jesuit priest received and intended to show at a conference. He wondered if he should develop this further, knowing that Coffman, his colleague at Loyola, and a documentarian, “knew how to do this in spades,” he told CNS.

They both were intrigued with the idea, but they faced some immediate challenges. For starters, there was only one filmed interview with O’Connor, and one short piece of her as a child (teaching a chicken to walk backward) and not many photos. Also, the Flannery O’Connor Trust would not allow dramatic reenactments of O’Connor’s work. In the end they settled on motion graphics to tell the stories of her works, which also pay tribute to O’Connor’s early work as a cartoonist. The directors also were able to recruit actress Mary Steenburgen to read some of O’Connor’s writings for the film.

Father Bosco had already been keeping tabs of anyone who spoke about O’Connor’s influence in interviews, including several authors, Conan O’Brien and Bruce Springsteen.

[hotblock2]

In a statement for the film’s award, Burns called it an “extraordinary documentary that allows us to follow the creative process of one of our country’s greatest writers.” He said it “provides us a glimpse into her life, including her Catholic faith, her unusual sensitivity to race as a Southern white woman, and her daily struggles with illness and the prospect and reality of an early mortality.”

He also expressed hope that “a new generation of readers will rediscover the writings of Flannery O’Connor because of this film.”

Father Bosco said he and Coffman were “obviously very pleased and honored” that Burns saw something in the film and they are happy to introduce, or re-introduce, O’Connor to viewers.

The priest said O’Connor’s writing reflects that “all of reality is a revelation of God’s grace.”

“Her stories are always haunted with this sense of mystery,” he added, bringing readers to a “place of uncomfortability” where they know there is something more going on and “are being asked to go on a journey of self-revelation.”

“She says very boldly: I write because I’m a Catholic,” but her works don’t have a sense of piety or triumphalism, he added, saying she focused more on the brokenness of society, especially in America, and even more particularly, in the South.

Coffman, who is not Catholic, said she “absolutely adores” O’Connor’s fiction.

“As we say in the film, she was writing for people who don’t believe in God. She wasn’t writing for the converts” but for people who need to face what’s in these stories.

And that’s something she and Father Bosco aimed to do with the documentary as well. With the film’s national broadcast, she said, “we were thinking of a secular crowd of belief and nonbelief, and I think the film accomplishes that.”

PREVIOUS: ‘The Sojourn’ is worth the trip

NEXT: Astronaut’s earthbound life veers off course in ‘Lucy in the Sky’

Share this story