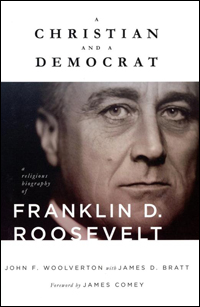

“A Christian and a Democrat: A Religious Biography of Franklin D. Roosevelt”

“A Christian and a Democrat: A Religious Biography of Franklin D. Roosevelt”

by John F. Woolverton with James D. Bratt.

Wm. B. Eerdmans (Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2019).

280 pp., $32.

Most Americans would not think of Franklin Roosevelt as one of our more religious presidents. The authors of “A Christian and a Democrat” would agree.

But they would argue that he was inspired by Christian beliefs that were ingrained in him in his childhood home and, perhaps, more importantly, at Groton, the boarding school he attended and that was led by the Rev. Endicott Peabody, an Episcopal priest and social progressive. Rev. Peabody was to remain a spiritual mentor to Roosevelt long after Roosevelt graduated from Groton.

[hotblock]

John F. Woolverton, the author of “A Christian and a Democrat,” writes: “Throughout his life, Roosevelt believed that Christian faith and democracy were inseparable.” To keep these ideals linked, Roosevelt adopted the “social gospel” of progressivism taught to all students of Groton by Rev. Peabody.

Coming from the wealthiest families of the country, they would be asked to envision and work for a future where class divisions would cease, where the seeking of material goods would be transformed into seeking spiritual development.

In short, they were being asked to live out Christ’s commandments to love their neighbors as themselves. But not in the traditional way, where the rich would do charity for the poor out of a sense of duty. Personal charity would be supplanted by “a system-wide practice embodied in law and supervised by official authorities, be they corporate or state.”

Woolverton contends that the principles of faith, hope and charity drawn from chapter 13 of Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians would be the chief inspiration for Roosevelt’s work as president. Hope was the driving force for Roosevelt from the time he contracted polio in 1921 through the first four years of his presidency in the depths of the Depression.

Charity on a national scale would be the moral force driving his presidency through the 1930s. Faith would become important in the years of the Second World War as America fought fascist dictators in Europe who saw themselves as godlike and the states they dominated as righteous utopias.

Roosevelt did not attend church often as an adult, but, interestingly, he remained the senior warden of his church in Hyde Park, New York, from 1928 until his death in 1945. He also enjoyed conversation on religious topics.

[hotblock2]

In February 1944, the White House invited a young Episcopal priest, the Rev. Howard Johnson, to dinner. Beside his parish duties, Rev. Johnson also taught courses on Soren Kierkegaard, the Danish philosopher and theologian, at Virginia Seminary. At dinner, Roosevelt brought up the subject of the evil of the Nazi regime and the Christian doctrine of original sin, a subject that puzzled him.

Rev. Johnson suggested that Kierkegaard might offer Roosevelt a better way to understand human evil. Most Americans believed in progressivism and evil was defined as a state of ignorance that the acquisition of knowledge could correct. Kierkegaard argued against belief in humanism and saw evil “as something ingrained, not just a slip owing to inexperience.” He maintained it was an individual’s responsibility to radically accept themselves as evil and to seek God’s forgiveness.

Forgiveness, in Kierkegaard’s view, is “the nature of God.” He would not accept that some people are more or less evil than others. Therefore, thinking of America as less evil than Nazi Germany would make no sense to Kierkegaard.

“A Christian and a Democrat” offers a new perspective on Franklin Roosevelt and is surprisingly readable and engaging. In our current age, it is refreshing to read about a president who did not speak often of his Christian beliefs but worked mightily to fulfill them.

***

Yearley attends the Ecumenical Institute of St. Mary’s Seminary and University in Baltimore.

PREVIOUS: ‘By the Grace of God’ explores clerical abuse with honesty, intelligence

NEXT: Pope and president acted according to ‘The Divine Plan’

Share this story