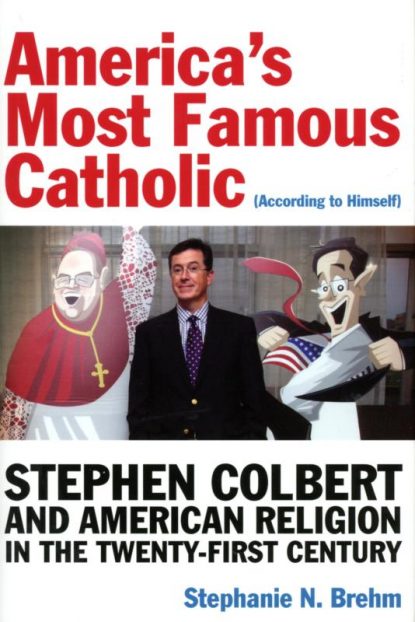

This is the book cover of “America’s Most Famous Catholic (According to Himself): Stephen Colbert and American Religion in the Twenty-First Century” by Stephanie N. Brehm. The book is reviewed by Loretta Pehanich. (CNS)

“America’s Most Famous Catholic (According to Himself): Stephen Colbert and American Religion in the Twenty-First Century” by Stephanie N. Brehm. Fordham University Press (New York, 2019). 256 pp., $30.

Anyone interested in religious comedy’s recent history in America will enjoy Stephanie Brehm’s book whose long subtitle better describes her work. “America’s Most Famous Catholic (According to Himself): Stephen Colbert and American Religion in the Twenty-First Century,” is a treatise on Catholic humor and its impact in the United States today.

Simultaneously entertaining and academic, the book is part of a series of publications on “the historical and cultural study of Catholic practice in North America” at Fordham University. It “springs from a pressing need in the study of American Catholicism for empirical investigations and creative explorations and analysis of the contours of Catholic experience.”

[hotblock]

Of course, Stephen Colbert’s cover shot and name in the title will attract more readers than an academic work normally would.

Using the popular Colbert (both the character he portrays and the man himself) as the unifying factor, the author covers Catholics in comedy and media prominence in recent history, from radio pundit Father Charles Coughlin, Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, and even Bing Crosby to Mother Angelica. Brehm includes Catholic (and formerly Catholic) comedians such as Don Novello (aka Father Guido Sarducci), Jim Gaffigan, Bill Murray, Jimmy Fallon, Louis C.K., Conan O’Brien, George Carlin and Jay Leno.

According to the author, “Colbert breaks all molds” as a master of satire, “an artistic form that ‘makes fun of human folly and vice by holding people accountable for their public actions.'”

This book highlighted for me the value of a celebrity whose deep faith doesn’t allow him to take himself too seriously nor claim to have all the answers. I enjoyed the brief biographical material (wished for more), which explained humor’s importance amid Colbert’s life traumas. His goal is clearly to entertain and make people laugh. These tools gave him perspective in his own suffering.

Brehm pointed out that Colbert’s comedy breaks down stereotypes of Catholicism as a rigid, somber, traditional institution and illustrates the intellectual, moral and pragmatic diversity it possesses.

While multiplicity and dissent have always existed in Catholic life and we no longer live in times of unquestioning obedience, Colbert’s comedy mocks the deep polarization and vitriolic dialogue so evident in our country today.

With a quarter of the U.S. population considering itself Catholic, Colbert helps us laugh at ourselves. Like a family member granted license to critique from the inside, Colbert uses humor to question hypocrisies and incongruities in our church. Brehm describes how Colbert walks a tightrope of poking fun without deriding the church he loves.

The author explains how the comedian also helps us better understand ourselves and the complexity of the church, which is based on faith and reason despite disunity of thought. “Colbert puts that paradox onstage,” Brehm writes.

It’s a modern behavior, the author contends, for a comedian to encourage self-reflection about religion through humor. We can relate to Colbert because he is like us: struggling, questioning, saying things we wish we’d dared to say, and wanting more accountability and collaboration with the hierarchy.

The secret of his success, Brehm says, is that he “does not diminish other’s search for meaning in different systems.”

At its heart the book is about comedy in the digital and social media age, which questions truth, connects us impersonally, blurs divisions and provides unlimited data via computers and phones.

Brehm uses Colbert to “provide insight into the mechanisms behind lived religion: the processes of meaning making and identity creation.” Thankfully, she also includes some of Colbert’s jokes. Brehm says that by delivering religious information in an entertaining way, audiences are covertly evangelized through his “stage as pulpit.” People may not be in the pews, but they catch “Church of Colbert” clips online.

Chapters cover Colbert as character, Catholic authority, catechist and culture warrior. His humorous personality, vacillating between silliness and influence, offers a serious take on Catholicism that has greatly influenced public perception. The entertainer is considered by many to be more trustworthy than contemporary politicians or world leaders, and Colbert is their leading source of news.

She contends that Colbert anesthetized Americans to extremism, blatantly making up facts that paved the way for President Trump’s election.

Brehm clearly did extensive reading and research on this entertainer, evidenced in 28 pages of footnotes. Expect some $10 words as the author provides a “digital media ethnography and rhetorical analysis” of Catholic comedy.

Despite being repetitive at times, the book is a worthwhile “case study of the intersection between lived religion and mass media” via Colbert. If you want to study how humor, social media and entertainment inform and mold our church and public opinion today, this book will be a good choice for you.

***

Pehanich is a Catholic freelance writer, blogger, spiritual director and former assistant editor for the Diocese of San Jose, California.

PREVIOUS: ‘Trolls World Tour’ brings the delightful diversion world needs

NEXT: ‘George W. Bush’ takes a mostly-warts view of president in PBS special

Share this story