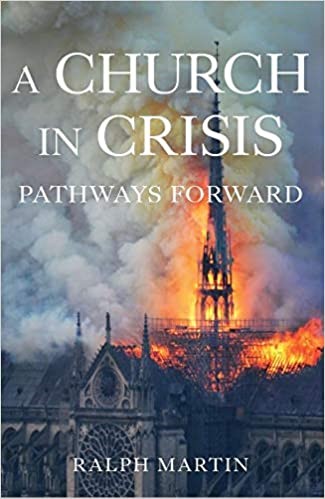

“A Church in Crisis: Pathways Forward.” by Ralph Martin. Emmaus Road Publishing (Steubenville, Ohio 2020). 536 pp., $22.18.

“A Church in Crisis: Pathways Forward.” by Ralph Martin. Emmaus Road Publishing (Steubenville, Ohio 2020). 536 pp., $22.18.

Ralph Martin, president of Renewal Ministries, director of graduate theology programs in evangelization and a professor of theology at Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit, has written an extraordinary book, “A Church in Crisis: Pathways Forward.” His analysis of this crisis, in a time of confusion and division, is comprehensive in scope, examining its ecclesial, doctrinal, and moral dimensions.

The book falls into two main parts: the first gives an in-depth analysis of these dimensions, and the second outlines pathways forward to attain “real and deep renewal in the Church.”

The three dimensions of this crisis are interdependent, that is, doctrinal and moral confusion will affect the ecclesial dimension of the crisis, and vice-versa. For instance, consider the “pastoral passivity of the bishops,” meaning thereby, according to Martin, “a remarkable silence regarding the areas of truth revealed by God that are most in conflict with our culture.”

The Church has failed to take seriously that the conflict confronting the Church today is a crisis of truth engaging the full spectrum of culture – powers, principalities, and organized centers of hostility. This passivity has rendered the Church, in many instances, a fence sitter, straddling the crucial issues of the day.

[hotblock]

Furthermore, Martin argues, “Catholics are cooperating with, and even welcoming, political and intellectual forces that are hostile to the Church. This has happened because many Catholics have begun to lose their grasp of and commitment to basic Christian truths.”

Throughout his book, Martin cites the Church’s pastoral passivity and accommodation to the sexual liberationist worldview. Examples of silence in these matters abound regarding sexual sins (e.g., cohabitation, homosexuality).

There is also general passivity or worse with regard to: universalism – the view that as a matter of either necessity or contingent fact, no one will end up in hell; evangelization (and conflation of it with “proselytism”); the eternal consequences of rejecting the Gospel; the de facto fostering of religious indifferentism; and the distinction between subjective and objective morality, the former dealing with the question of responsibility and the conditions under which a person is to be held morally responsible.

At the root of the ecclesial crisis is the confusion, resulting in a dualism, between what John Paul II called “the coexistence and mutual influence of two equally important principles [of mercy and truth]” (Reconcilatio et Paenitentia,§34), and what Martin describes as the “conflict between objective truth and actual life, between the clarity of truth and the depth of compassion.”

In the light of the Catholic ecclesiology, we can understand that these two equally important principles of mercy and truth are grounded in the Church’s nature as both Mother and Teacher (see John Paul II, Familiaris Consortio, §33; Catechism of the Catholic Church §§2030-2051). But this ecclesiological reality has also been divided by pastoral passivity. Martin urges that all in the Church “need to preach [and teach] clearly and boldly the call to repentance and conversion.”

At the root of the moral crisis, as analyzed by Martin, is the confusion regarding a set of conceptual distinctions first introduced by John Paul II in helping us to understand the dynamics of moral progress, namely, the “law of gradualness” and the “gradualness of the law.” (Familiaris Consortio §34)

The former is unproblematic when it is properly understood that the Church must be sensitive to a person’s moral progress, namely, that he is striving to become good by stages of moral growth, understanding sin, weakness, and confession (cf. 1 John 1:9).

The “gradualness of the law” is deeply problematic because it understands the role of the moral law in the Christian life in such a way that it turns the obliging force of the law into an aspiring force, rendering the moral law a mere ideal.

Furthermore, this view of the law erroneously holds that there are “in divine law various levels or forms of precept for various person and conditions” (Familiaris Consortio, §34). This tilts the moral law into a version of situation ethics, which has caused widespread confusion and raised concern about the diminishment of Church teaching about sexual morality.

Martin rightly insists that fundamental to the doctrinal crisis of the Church is the “question of revelation.” He explains: “Has God revealed himself? If so, how can we have access to what he reveals? If we can have access to what he reveals, how can we discern true ‘development’ from false development in our understanding of the truths of faith?”

Now, new theories of revelation in the last century did not deny that God has revealed himself, but they have opposed the notion of God revealing himself and propositional truths, that is, revealed truths.

Indeed, this opposition grants only a secondary status to theological propositions. The latter are supposedly formulated on the basis of an experience of the living God, but there is as such no revealed truth concerning God, man, salvation, the world, and so forth. Hence, revelation is not “a source of certain truth and … reliable guidance for our lives.” This idea of revelation has become something like a consensus in the last century or so.

By contrast, Martin re-affirms Dei Verbum §2’s statement that God’s “plan of revelation is realized by deeds and words having an inner unity.” Thus, God’s special revelation is constituted by its inseparably connected words (verbal revelation) and deeds, intrinsically bound to each other because neither is complete without the other. The historical realities of redemption are inseparably connected to God’s verbal communication of revealed truth. Without this idea of revelation, we lack a solid place to stand.

This idea of revelation is also necessary to counter “a nebulous understanding of ‘development’ that seeks to weaken the clarity and certainty of revealed truth, leading in some cases to an actual reversal of the explicit teaching of Jesus as it has been understood in the Church for almost two thousand years.”

Martin’s book is a tour de force. In the words of Cardinal Gerhard Müller, “An important book that should be widely read.”

***

This column first appeared on the website The Catholic Thing (www.thecatholicthing.org). Copyright 2020. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

PREVIOUS: Nintendo scores family-friendly hit with new ‘Super Mario’ game

NEXT: ‘Nomadland is ‘The Grapes of Wrath’ for our times

Share this story