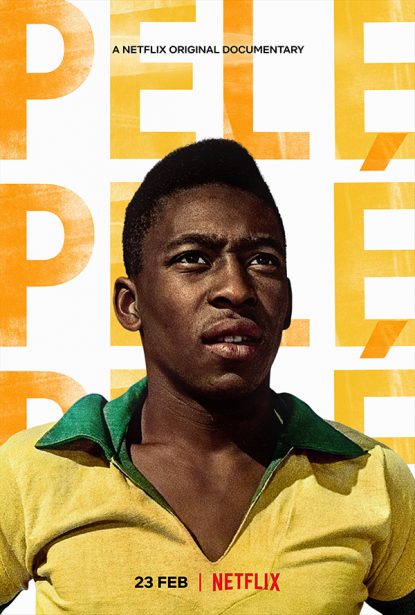

This is the TV poster for “Pele,” which streams on Netflix Tuesday, Feb. 23, 2021. (CNS photo/Netflix)

NEW YORK (CNS) — Arguably the greatest soccer player of all time, and said to have been, at one stage of his career, the highest paid athlete in the world, Edson Arantes do Nascimento is the subject of a two-hour profile under the name by which he’s far better known: Pele.

Filmmakers Ben Nicholas and David Tryhorn’s biography begins streaming on Netflix Tuesday, Feb. 23.

Their documentary is a touching portrait of the man who gave his sport its nickname, the beautiful game. Yet, just as Pele’s relationship to his Catholic faith is marked by ambiguity, devout in belief but significantly flawed in action, so their politically belabored film fails to take a consistent stand with regard to the role he played in the troubled recent history of his Brazilian homeland.

Along with the occasional expression resonant of a locker room, the program is marked by such mature themes as political repression, poverty, racism, adultery and out-of-wedlock pregnancy. At least some parents may nonetheless feel that the insights the show gives make it worthwhile as well as acceptable viewing for mature teens.

An extended interview with the 80-year-old legend frames Nicholas and Tryhorn’s narrative, which largely focuses on Pele’s participation in the quadrennial World Cup tournament between 1958 and 1970. Many in the audience may be startled to see that the star player, whose exceptional achievements largely depended on his strong and agile legs, now relies on a walker.

[hotblock]

A curious irony unites the beginning and end of Pele’s time on the international scene. When he made his first World Cup appearance in Sweden, observers said he was too young to live up to expectations. Twelve years later, they murmured that — at the advanced age of 29 — he was too old to produce results.

In both instances, the outcome was the same: victory for Brazil. Pele’s initial triumph helped exorcise the legacy of his team’s defeat at the hands of Uruguay eight years earlier. Similarly, his final one served to redeem his country’s indifferent performance in the 1966 World Cup.

Pele’s 1958 exploits made the teenager, in the words of musician Gilberto Gil, “the symbol of Brazil’s emancipation.” Yet, says journalist Paulo Cesar Vasconcellos, “off the pitch,” the star “was known for his political neutrality.” After a 1964 military coup, Pele drew criticism from those who felt he should have spoken up forcefully against the oppressive new regime.

Pele was compared to boxer Muhammad Ali, who famously refused to be drafted during the Vietnam War. But the Brazilian lacked Ali’s freedom of expression. “Dictatorships are dictatorships,” as journalist Juca Kfouri puts it.

Given soccer’s global status — with an estimated 3.5 billion fans worldwide, its popularity dwarfs that of other sports — it may be fair to ask why Pele wasn’t bolder in making use of his influence. Yet Nicholas and Tryhorn seem to want to have it both ways: They implicate Pele for failing to protest, but also ask viewers to overlook his apparent hesitancy to do so.

Still, when it works well, as it does in covering other aspects of its subject’s remarkable life, the film fully justifies the tribute celebrated coach Mario Zagallo pays to his former teammate. “Pele,” Zagallo says, “was everything imaginable.”

***

Byrd is a guest reviewer for Catholic News Service.

PREVIOUS: Don’t let its size intimidate you; this is a great book on prayer

NEXT: Nintendo scores family-friendly hit with new ‘Super Mario’ game

Share this story