NEW YORK (CNS) — Most people associate fall with the turning of leaves. But at PBS, autumn usually means the launch of an ambitious Ken Burns series that serves to usher in a new TV season.

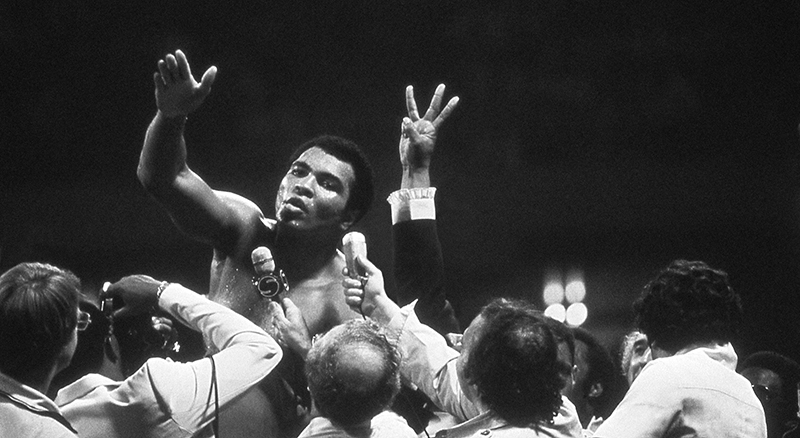

Numerous Burns documentaries with September debuts can be assigned to this category, ranging from his masterpiece, 1990’s “The Civil War,” to “Country Music” from 2019. This year, “Muhammad Ali” takes its place among them.

The show, which reflects the distinguished filmmaker’s high artistic standards, premieres on PBS Sunday, Sept. 19, 8-10:30 p.m. EDT. Subsequent episodes of the four-part series will air 8–10 p.m. EDT on consecutive nights, concluding Wednesday, Sept. 22. Broadcast times may vary, however, and viewers should consult their local listings.

[hotblock]

As he did for 2012’s “The Central Park Five,” Burns co-directs this admirable, though not especially revealing, profile with his daughter Sarah and her husband, David McMahon. The trio also co-wrote the series.

Mature themes — including war, poverty, racism, physical abuse aimed at spouses and children, and adultery — extensive graphic boxing footage and occasional off-color language all suggest an adult audience. Given its educational value, however, some parents may consider “Muhammad Ali” acceptable for mature teenagers.

The program traces both the professional ups and downs and the spiritual journey of the legendary pugilist who was born Cassius Clay on Jan. 17, 1942. After winning Olympic gold as a light heavyweight at the 1960 Summer Games in Rome, the Louisville, Kentucky, native fought his first professional bout at his hometown’s Freedom Hall on Oct. 29 of that year.

At about the same time, he first became acquainted with the Nation of Islam while on a visit to Harlem to meet his idol, fellow boxer Sugar Ray Robinson. Despite its name, the group preached a creed — including the separation of the races and the prophetic status of its leader, Elijah Muhammad — that differed significantly from the traditional faith of Muslims.

Malcolm X, minister of the NOI’s most prominent mosque, was instrumental in Clay’s ultimate embrace of the organization, which came in the wake of his defeat of Sonny Liston for the world heavyweight championship in early 1964. Two days after that landmark fight, the new champ declared, “I believe Allah is the true God.”

And, with that, biographer Jonathan Eig says, “Muhammad Ali was born.”

[hotblock2]

His membership in what author and professor Gerald Early terms an “appealing but dangerous cult,” made Ali appear “un-American” to many. He was viewed, in the words of the screenwriters, as “ungrateful and offensive and a threat that needed to be stopped.”

Such enmity only worsened in 1966 when Ali declared himself a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War. “I will not go 10,000 miles to help kill innocent people,” he proclaimed.

Stripped of his boxing license, Ali lost three-and-a-half years in the prime of his career. Eventually, however, The Greatest — as Ali famously characterized himself — succeeded in reclaiming his title from George Foreman in Zaire on Oct. 30, 1974.

The evocative photographs and rare archival footage that constitute Burns’ trademark are on full display here. But audience reaction to this biography may depend on how much viewers already know about Ali’s life as well as on their attitude toward boxing.

Those new to the subject will likely find Burns’ work absorbing. Yet the documentarians’ linear approach, moving from one match to the next, often feels redundant. And protracted sequences inside the ring feel more appropriate to an ESPN special than a PBS production.

As a result, at least some TV fans will likely be left wishing Burns and his collaborators had focused more on Ali the activist and humanitarian. Given that more than a dozen films have already been made about Ali, moreover, it may simply be that, as sportswriter Dave Kindred puts it, “the magic is gone.”

***

Byrd is a guest reviewer for Catholic News Service.

PREVIOUS: Analysis of church’s diplomatic work is a must-read for many

NEXT: Poet sees renewed appreciation of fine arts as way to deepen devotion

Share this story