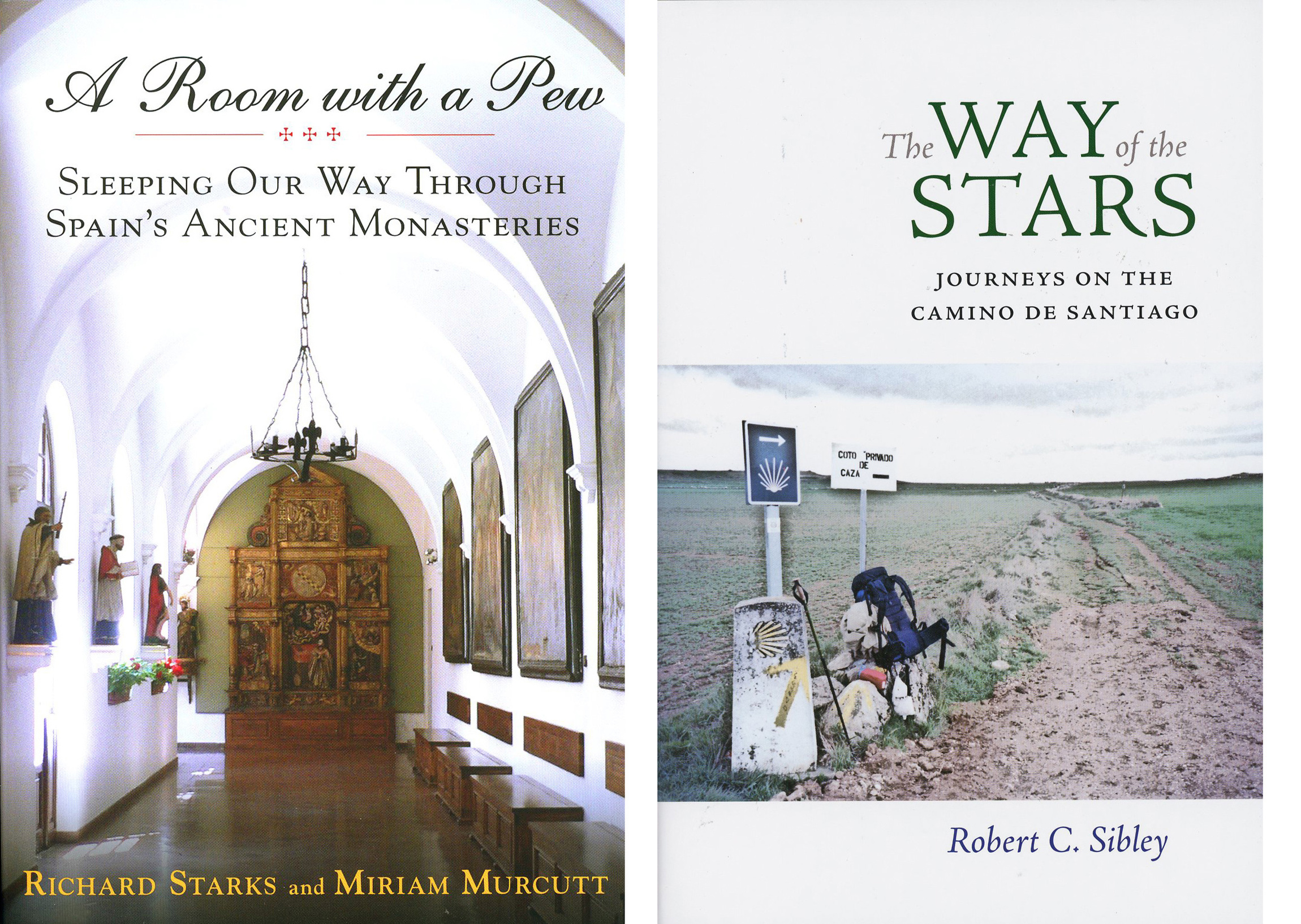

“A Room with a Pew: Sleeping Our Way through Spain’s Ancient Monasteries” by Richard Starks and Miriam Murcutt. Globe Pequot Press (Guilford, Conn., 2012). 244 pp., $16.95.

“The Way of the Stars: Journeys on the Camino de Santiago” by Robert C. Sibley. University of Virginia Press (Charlottesville, Va., 2012). 170 pp., $23.95.

Like early 20th-century anthropologists projecting their own nonsensical theories onto South Pacific islanders, Richard Starks and Miriam Murcott — authors of “A Room with a Pew” — descend on Spain’s monasteries with their anti-church baggage.

Offering a constant barrage of worn-out sneer, their trite and misinformed observations leave one with the impression that they get their history from Dan Brown novels.

Their unfounded and outdated nonsense on countless aspects of Catholic history, such as the Spanish Inquisition, confuse modern terms with the past: “As often as not, the burnings were preceded by forced confessions, wrung out of hapless victims by water-boarding and other tortures.” The authors also echo the Enlightenment’s anti-medieval bias, referring to the era of magnificent, religiously inspired cathedrals, artwork and poetry such as Dante’s “Divine Comedy” as being ignorant.

Religion thrives only in an ignorant epoch, the authors reason. They then condescend further: “Knowledge, of course, keeps on increasing, while for some, faith remains fixed, locked into the past. Today, knowledge has increased to such an extent that reconciliation with faith is all but impossible.”

Traditional religion turns us away from the ego and narcissism, and toward fellowship and charity with others as a reflection of a deeper love and fellowship with God. If anything, Sibley shows the boredom of a narcissistic and solipsistic life, just like Starks and Murcott remind us of the nasty humorlessness behind much anti-church wit.

Ironic words about knowledge given the authors’ warped understanding of church history and Catholic spirituality. The writing might harm the church if it weren’t so mediocre and cheap. Thus the authors characterize the Council of Trent’s aim as “to redeem a Catholic Church that, by the 16th century, had become thoroughly corrupt, exhibiting the sexual mores of a Casanova and the moral probity of a Goldman Sachs.” Surely this sort of writing must be embarrassing even to other anti-church folk.

Intellectually and spiritually empty, the book’s stream of predictable cliches and cheap comparisons tire: They see nuns “striding down the hill toward us … (with) their long habits fluttering behind them like Superman capes;” a monk enters the church, “his bald head rising above it (the organ) like the dome of a speckled brown egg”; other monks remind the authors of Humphrey Bogart or the living dead. Not content with the monks and nuns, the authors heartlessly refer to a tired-looking parishioner as “a recovering alcoholic” several times.

The authors make a caricature not out of the Catholic Church as they clearly intend, but out of themselves as cynical, too-smart-for-religion jokesters. When they write that tourists in one monastic gift shop “stare with that glazed-eye expression that comes over people who’ve spent too much time looking at Virgin Mary fridge magnets,” the reader can only wonder who would find such puerility funny.

“The Way of the Stars,” journalist Robert C. Sibley’s take on El Camino, the medieval pilgrimage route normally followed from southern France over the Pyrenees and then to Spain’s Santiago de Compostela, offers a much more respectful view. But he too reflects the thoughts of our modern, post-Christian world and thus offers little to serious Catholics.

His quest — more New Age self-promotion and self-growth than religious pilgrimage — makes the book autobiographical rather than religious. Perhaps this self-absorption is what “spiritual” means nowadays. Most sentences seem to start with “I.”

He fails to move beyond himself — the whole point of the Camino and of traditional religion — and offers meaningless passages exemplified by the following: “I showered and changed and went out looking for food. I wanted fried chicken but settled for a couple of ham bocadillos and a bottle of Estrella Damm at the Bar Chomin. … I was comfortable and oddly content to listen to the indecipherable chatter of the other patrons and let the memories drift as they pleased. I ordered another beer.”

Who cares.

Traditional religion turns us away from the ego and narcissism, and toward fellowship and charity with others as a reflection of a deeper love and fellowship with God. Sibley remains entirely immersed within his ego, though he does offer the usual platitudes about living more in the moment and working through physical and psychological pain and suffering. Yet this self-referentialism shows once again that the pilgrimage, more of a trek in fact, was simply an exercise in psychological gymnastics for the author.

If anything, Sibley shows the boredom of a narcissistic and solipsistic life, just like Starks and Murcott remind us of the nasty humorlessness behind much anti-church wit.

***

Welter is studying for his doctorate in systematic theology and teaching English in Taiwan.

PREVIOUS: Film on Roosevelt echoes theme of ‘morals don’t matter’

NEXT: Gun violence leads to closer scrutiny for links with media violence

Share this story