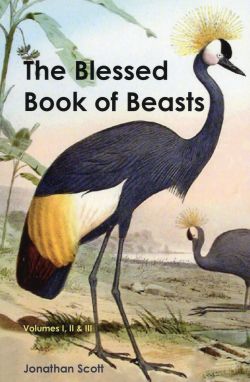

“The Blessed Book of Beasts”

“The Blessed Book of Beasts”

by Jonathan Scott.

Eastern Christian Publications (Fairfax, Virginia, 2014).

221 pp., $19.95.

This is a book for parents to read to and with their children. A bestiary, the author explains in his introduction, was a medieval, illuminated manuscript about animals mentioned in the Bible, and some not mentioned, but creatures of fantasy.

Devotional in intent, poems were written about the various creatures, verses that aimed to teach moral and spiritual lessons, imaginative lessons to bring home to the readers theological truths in a vivid way.

In this, the bestiary is akin to the stained-glass windows of medieval churches, which illustrated biblical stories and the lives of the saints to assist the faithful, who were often illiterate, in understanding better the Christian faith. Various saints such as Francis de Sales, the author notes, used stories of animals to teach profound truths.

Jonathan Scott’s “The Blessed Book of Beasts,” one of the first bestiaries to be produced in centuries, is organized in three “volumes,” roughly corresponding to the order of creation in the first chapter of Genesis.

These are the creatures of the sea and crawling creatures, such as insects and snakes; creatures of the air and the field; and larger creatures of the land and forest, mainly mammals. The very last creature in the book, not surprisingly in a Christian work, is the lamb, traditionally associated with the exodus of the Jews from Egypt, and with the sacrifice and redemption of humanity in Jesus’ death and resurrection.

[hotblock]

Each entry includes an illustration of the creature itself, accompanied by a biblical verse from the Hebrew Scriptures and/or the New Testament, which refers to the creature and derives a lesson from it. Scott adds to each a four-line poem of his own writing. Sometimes he stretches a bit to make his point, but the result is well worth it.

He states, for example, that the Douay-Rheims translation of Verse 11 of Psalm 91 mentions a unicorn, where the original Hebrew and other translations do not. He notes quite accurately, however, that the unicorn was a symbol of Christ in the Middle Ages, with its horn understood to have healing powers, as Jesus healed people in his own time, a metaphor for the healing of sin through Christ.

His resulting verse conveys a theological truth: “If you’re wounded, trust the Unicorn, to heal you with its one, majestic horn. In unity with Christ, entrust your soul. Be one in Christ, and Christ will make you whole.” He cites appropriately, Chapter 6, Verse 19 of St. Luke’s Gospel and Chapter 12, Verse 5 of the St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans, stressing the healing power of Jesus’ touch and Paul’s assertion that we are, as church, “one body in Christ.”

The exchanges that can occur between adults and their children, I believe, will be the occasion for sharing, and as the author hopes, for deepening the faith of both.

***

Fisher is a professor of theology at St. Leo University in Florida.

PREVIOUS: Experts, historians explore Shakespeare’s Catholic sympathies

NEXT: Movie review: Before I Go to Sleep

This is a very good book. It is good to see someone writing good poetry again, in a way that sheds light on the mysteries of the Christian Faith. Thank you for reviewing this book.