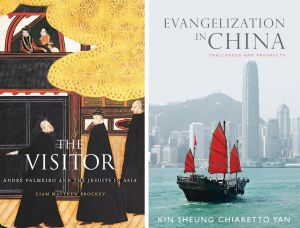

“The Visitor: Andre Palmeiro and the Jesuits in Asia” by Liam Matthew Brockey. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2014). 528 pp., $39.95.

“The Visitor: Andre Palmeiro and the Jesuits in Asia” by Liam Matthew Brockey. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2014). 528 pp., $39.95.

“Evangelization in China: Challenges and Prospects” by Kin Sheung Chiaretto Yan. Orbis Books (Maryknoll, New York, 2014). 178 pp., $30.

Taken together, these two books provide a clear introduction to Christianity in China, particularly from the 16th century onward.

“The Visitor,” in fact, takes a much broader scope than China. Author Liam Matthew Brockey, an associate professor of history at Michigan State University, traces the career of Portuguese Jesuit Father Andre Palmeiro, as he rose through the academic ranks at the leading Portuguese Jesuit colleges before being sent overseas at the age of 49.

The author excels at situating the priest within his society and order and brings readers right into the thick of the action:

“On the orders of the count-bishop, the cathedral chapter arranged a citywide procession for the first Friday after the octave of Corpus Christi. On that day in early June the prelate carried a monstrance draped with a black silk veil from the cathedral through the streets of Coimbra, up to the university and down nearly to the riverbank. ‘More people than had ever been seen in the city’ joined in the procession, forming a crowd so large that its front and back ends passed each other on the city’s main thoroughfare,” Brockey writes.

[hotblock]

“The Visitor” thus shows the importance of religion and culture. This interplay becomes important when we see Father Palmeiro in Hindu India and later in China, whose cultures were decidedly not Christian. Father Palmeiro as visitor to these areas carried the heavy responsibility of ensuring that the spirit of the order and its original charism were being faithfully lived out, even with the vast distances involved.

The most pressing issue was the extent to which Jesuits could immerse themselves and the Gospel in the local cultures. Could Jesuits, for instance, dress up as Hindu holy men or, in China, as mandarins, in order to fit in with the society’s leaders? And was it right for the order to focus so much on the upper classes?

The book’s downside is that Brockey rarely lets the major figures speak directly to us today, as he describes what they wrote rather than putting primary writings, such as letters and reports to Rome, into the book’s text.

“Evangelization in China” begins with a historical and cultural perspective, giving readers a strong sense of Chinese culture and history, which differ so greatly from that of the West. The country must be accepted on its own terms, rather than be seen through a Western lens if Christianity is to spread. It must be a Chinese Christianity, rather than a westernized one.

The three most influential spiritual and philosophical systems in China — Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism — interacted with each other in a way that seems strange to the Western perspective, since rather than being at odds, they complemented one another. Broadly speaking, the first offers a transcendent perspective, the second focuses on humans within nature and the cosmos, and the last one teaches proper social relations. Harmony is the great underlying assumption of Chinese culture, and all three religions worked toward this on different levels.

Christianity is thus something of an intrusion into Chinese cultural space, though author Kin Sheung Chiaretto Yan shows the possibilities for its growth. China, again unlike the West, never developed a sphere for religion independent of the state. Religion was always a tool of the ruler, often used for moral teachings. The Catholic Church has had bumpy relations with the Chinese government in recent decades. not only because of the communist ideology of the party, but also due to the basic assumptions in church-state relations.

Taking a mostly Catholic perspective, Chiaretto Yan examines papal attempts at dealing with Chinese culture and politics. He raises some tough questions: “It is worth noting that while many in China might be interested in Christianity, they are hesitant to approach a church entangled in controversy with the government. Why is it that other Christian churches are growing, except for the Catholic Church?”

The author also laments the lack of priestly vocations in China, as its seminaries are almost as empty as in Western countries. On the bright side, they have begun offering courses in continuing education for women religious and priests.

Chiaretto Yan offers no easy solutions, and ends up putting things in the hands of the Holy Spirit, perhaps the only solution available to Chinese Christians at this time.

***

Welter has degrees in history and theology, and teaches English in Taiwan.

Share this story