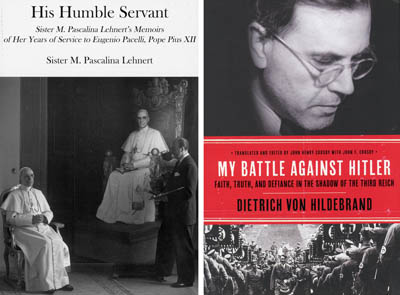

These are the covers of “My Battle Against Hitler” by Dietrich Von Hildebrand and “His Humble Servant: Sister M. Pascalina Lehnert’s Memoirs of Her Years of Service to Eugenio Pacelli, Pope Pius XII” by M. Pascalina Lehnert. The books are reviewed by Graham Yearley. (CNS)

“My Battle Against Hitler” by Dietrich Von Hildebrand, presented by John Henry Crosby with John F. Crosby. Image Books (New York, 2014). 327 pp., $28.

“His Humble Servant: Sister M. Pascalina Lehnert’s Memoirs of Her Years of Service to Eugenio Pacelli, Pope Pius XII” by M. Pascalina Lehnert. St. Augustine Press (South Bend, Indiana, 2014). 214 pp., $18.

***

“My Battle Against Hitler” and “His Humble Servant” are two memoirs of German Catholics who both resisted the totalitarian menace of Nazism.

Von Hildebrand was a Protestant who became Catholic, a professor of philosophy and an ardent critic of National Socialism from its formation in the beer halls of Munich in the early 1920s until its defeat in 1945.

Sister M. Pascalina Lehnert belonged to the order of the Teaching Sisters of the Holy Cross and, starting in 1918, she worked as a housekeeper and eventually as an adviser to Eugenio Pacelli, when he was the papal nuncio to Germany. During World War II, when Cardinal Pacelli had been elevated to the papacy, he instructed Sister Pascalina to direct his clandestine services to hiding and supplying the thousands who had turned to the Vatican for help.

Von Hildebrand displayed from an early age a remarkable independence from the ideologies and prejudices of his time. Born in 1889 into a wealthy and artistic family (his father was a noted sculptor), the Von Hildebrands were nominal Protestants who baptized Dietrich, their only son, as was expected of members of their class.

[hotblock]

But Dietrich displayed from a young age a fervor for religion uncharacteristic of his family. When taken to a Catholic church to view the paintings and sculptures as a child, he ignored the art and was seen genuflecting and praying at every station of the cross.

He despised all forms of anti-Semitism, even the milder forms commonly shared by most German Catholics and Protestants. He valued the integrity and holiness of individuals in a time when both fascism and communism saw the value of an individual as part of a collective mass serving the state. He recognized early that National Socialism appealed to the darkest instincts of Germans for militarism, ultra-nationalism and anti-Semitism at a time when Germany had been beaten and humiliated by the Allies.

Von Hildebrand started studying philosophy in 1906 and was a student of Edmund Husserl, one of the progenitors of phenomenology. Eventually, Von Hildebrand taught philosophy at the University of Munich through the 1920s until he was forced to flee Germany in 1933 to avoid arrest for his open opposition to Nazism.

He resettled in Vienna, and began a weekly newspaper, Der Christliche Standestaat (The Christian Corporate State), dedicated to attacking the falseness of Hitler’s intellectual underpinnings for National Socialism. In 1938, Von Hildebrand and his wife were forced to flee Austria when Hitler annexed it. They went first to Switzerland, then France, and on to Portugal where they sailed first to Brazil and then the United States in 1940. Von Hildebrand would become a faculty member at Fordham University in New York, teaching there until 1960. He would continue to write and publish until he died in 1977.

Although Von Hildebrand was one of the earliest critics of Hitler and courageously kept up his opposition when many equally hostile to Nazism kept quiet, he was not well known and was content to remain that way, not seeing his work as anything extraordinary. The publication of “My Battle Against Hitler” is an attempt to bring the work of this remarkable man to the public.

The first two-thirds of the book is a memoir he wrote for his second wife, Alice Jourdain, who met Von Hildebrand years after he fled Germany and Austria. The remaining third is a collection of essays from Der Christliche Standestaat on the anti-personalism of modern states and ideologies, the menace of quietism, and the profound sin of anti-Semitism. The memoir is a whirl of theologians and philosophers and friends all largely unknown to contemporary readers, but the essays still have the sting of righteous anger and show the courage of a man willing to face up to evil and call it evil.

Sister Pascalina served as housekeeper and later as a personal adviser to Pope Pius XII for 40 years. Less than a year after Pius XII died, Sister Pascalina wrote her memoir, titled in English “His Humble Servant” but more accurately translated from the German as “I Was Allowed to Serve Him.” The motive for her memoir was to honor the man who had been her employer from 1918 to 1958.

Her memoir is a stream of adulation for Pope Pius, in whom not the smallest fault is found. Eventually, her credibility is undermined by her devotion.

Sister Pascalina outlived the pontiff by 25 years and long enough to experience the questioning of Pope Pius’ seeming lack of action and vocal opposition to Nazism during the Holocaust. Sister Pascalina passionately argued that the pope saved hundreds, if not thousands, of lives and provided direct support and relief to those in hiding from the Germans. She argued that Pope Pius believed that speaking out directly in criticism of Hitler would only result in more Catholics and Jews dying.

Pope Pius did make several statements against the persecution of Jews and Catholics. Sister Pascalina, at the direction of the pope, supervised the vast relief effort to Romans and people in hiding. What she does not mention is that she herself had become famous and that she was faced with similar allegations. Her last years were difficult and she hoped that the English translation of her book would help to restore Pope Pius’ reputation. It was not completed at the time of her death on Nov. 13, 1983.

Most of the more scandalous charges against Pope Pius have been refuted, but his reputation has never been restored and questions remain. One of the unintended results of reading “His Humble Servant” is that it compels readers to read further about Pope Pius and the Second World War. “Pius XII and the Holocaust” by Jose M. Sanchez and “Pius XII and the Second World War” by Saul Friedlander are both balanced and thoughtful assessments of this controversy.

Also of interest is “Pope Pius XII and World War II: The Documented Truth: A Compilation of International Evidence Revealing the Wartime Acts of the Vatican,” compiled and edited by Gary L. Krupp, fourth edition. Pave the Way Foundation (New York, 2014). 332 pp., $62.49.

***

Yearley is a graduate of the Ecumenical Institute at St. Mary’s Seminary and University in Baltimore.

PREVIOUS: ‘The Matrix’ creators raise up a galactic ‘Wizard of Oz’

NEXT: ‘Whiplash’ crosses the line with abuse-as-education storyline

Share this story