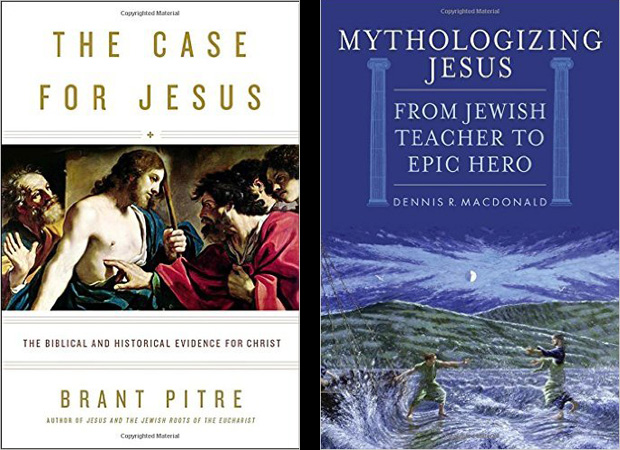

“The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ”

by Brant Pitre.

Image Books (New York, 2016).

256 pp., $23.

“Mythologizing Jesus: From Jewish Teacher to Epic Hero”

by Dennis R. MacDonald.

Rowman & Littlefield (Lanham, Maryland, 2015).

164 pp., $34.

Brant Pitre, a professor of sacred Scripture at Notre Dame Seminary in New Orleans, packs a great deal of information into his new book, “The Case for Jesus,” as he aims to refute the scholarly argument that the four Gospels were anonymously written after decades of only spoken transmission of stories about Jesus. Such an argument amounts to an attack on the reliability of the Gospels.

Pitre shoots many holes in this theory, noting for instance “the utter implausibility that a book circulating around the Roman Empire without a title for almost a hundred years could somehow at some point be attributed to exactly the same author by scribes throughout the world and yet leave no trace of disagreement in any manuscripts. And, by the way, this is supposed to have happened not just once, but with each of the four Gospels.” In addition to this sort of reasoning, Pitre turns to the church fathers and their unanimity about the Gospels’ authorship.

[hotblock]

He takes readers through the New Testament, comparing the synoptic Gospels with each other and with John’s Gospel. He shows just how closely the New Testament follows from the Old. The New Testament cannot be understood by itself, because it brings to fruition the Old Testament, he says.

This is most clear when Pitre examines certain claims Jesus makes about himself, such as being the “Son of Man.” This term comes from the Old Testament’s apocalyptic Book of Daniel and expresses Daniel’s concept of the kingdom of God: “in the Book of Daniel, the son of man is a heavenly king ruling over a heavenly kingdom” Pitre ties this in with Daniel’s “mysterious prophecy of the death of the Messiah.” The two concepts, the messiah and a divine being, are brought together in Daniel.

Pitre’s discussion of the Transfiguration, and why Moses and Elijah appear with Jesus, also makes for satisfying reading.

“The Case for Jesus” thus serves a great purpose to many Christians who read the New Testament but tend to avoid much of the Old. The book could give many Christians a renewed appreciation for the Old Testament. Pitre convincingly argues that we can only understand Jesus and the New Testament from the Old Testament and first-century Jewish culture. In addition, a knowledge of Greco-Roman culture, especially the first-century genre of biography, helps modern readers understand that the Gospels were, in fact, ancient biographies of Jesus.

Given the lively nature of New Testament scholarship, perhaps it should come as no surprise that “Mythologizing Jesus” strongly counters Pitre’s idea of the Gospels as biographies. Dennis R. MacDonald, a professor of New Testament and Christian origins at the Claremont School of Theology in California, regards much of the Gospels of Mark and Luke as little more than rewrites of ancient Greek myths in attempts to turn the historical Jesus into a greater superhero than the ancient gods and goddesses were.

Pitre, for his part, warns against reading too much of the modern mindset into the New Testament, such as by judging the Gospels as biographies according to the contemporary understanding of biography. MacDonald’s “superhero” approach exemplifies precisely this error.

While Pitre practices exegesis, drawing out the texts’ meaning, MacDonald seems to practice eisegesis, imposing his preconceived notions on the text. He tries to find parts of Mark and Luke that parallel more ancient Homeric and other Greek writings to convince the reader that Luke and Mark are basically Homeric renderings of Jesus.

His weak and confusing examples ruin his case. One section of Homer’s “Odyssey” finds a supposed later echo in Mark: “Odysseus arrived on the island of the Phaeacians naked and starving”; “Jesus arrived in Judea without money or a host.” Homer’s “Illiad” was supposedly recycled in Mark: “Zeus mourned the death of Sarpedon”; “Jairus … asked Jesus to heal his daughter. Later she dies.” Such snippets are merely vague echoes of each other.

MacDonald’s parallel reading of Luke and Mark with various pre-Christian writings fails to convince. It is like claiming that NASA’s moon landings did not occur because of the many parallels between those news stories and earlier science fiction novels that tell of landings, astronauts, and a return to the mother ship or original planet after some scientific activity.

Pitre’s book works because he uses reason to show how the orthodox faith makes sense, in this case as applied to genre studies, biblical studies and history. “Mythologizing Jesus” is yet another attempt at reducing Jesus to a mere human, the Trinity to myth, and Christianity to good feelings and ethics. It is a failed use of reason.

***

Also of interest: “Searching for Jesus: New Discoveries in the Quest for Jesus of Nazareth — and How They Confirm the Gospel Accounts” by Robert J. Hutchinson. Thomas Nelson, an imprint of HarperCollins Christian Publishing (Nashville, Tennessee, 2015). 352 pp., $24.99.

***

Welter has degrees in history and theology, and teaches English in Taiwan.

PREVIOUS: How did DeNiro end up in a sexploitation flick like this?

NEXT: ‘The 5th Wave’: Not even invading aliens are a match for teen angst

Share this story