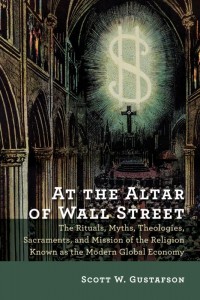

“At the Altar of Wall Street: The Rituals, Myths, Theologies, Sacraments and Mission of the Religion Known as the Modern Global Economy”

“At the Altar of Wall Street: The Rituals, Myths, Theologies, Sacraments and Mission of the Religion Known as the Modern Global Economy”

by Scott W. Gustafson. Wm. B. Eerdmans

(Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2015).

232 pp., $22.

As the song from the musical “Cabaret” puts it, “money makes the world go round.”

According to Scott W. Gustafson in his book “At the Altar of Wall Street,” money not only makes the world go round but it also is the foundation of all religions, and is itself a religion. Throughout the book’s eight chapters Gustafson explains the rituals, myths, theologies, sacraments and mission of the world’s economy.

A theologian, teacher, Lutheran pastor and an investor who “achieved ‘spiritual’ ecstasies” from investing that he had “never quite felt through more traditional religious experiences,” Gustafson provides an insightful look into the history and tradition of the economy, and how economics has become the common religion for the world “because it functions in our culture as religions have functioned in other cultures.”

The purpose of this book, Gustafson writes, is “to describe how economics functions as a religion in our emerging global culture.”

[hotblock]

According to Gustafson, the language of economics runs like a ribbon through religious thought. He notes that in most if not all religions, the debt we owe God is a central tenet of faith. He emphasizes that this concept of debt originates early in human history when people moved from being hunter-gatherers who apparently (no proof is offered here) shared all things in common, to living in fixed communities, where the concept of private ownership of property created the need for a system for keeping track of what was owned and owed.

Throughout the book, Gustafson provides insights into the connection between religion and the economy that are very engaging. His definition of myth, “a story that happens outside common time which explains phenomena inside common time,” and religion, “a cultural attempt to interpret known facts in a meaningful way,” are clear and helpful.

Some of his comments are quite bold, and at times, disconcerting.

Some examples: “Nonetheless, the collectivizing acts of the Soviet Union mimic actions of religious terrorists who adhere to their religious principles despite the carnage”; “But morality achieves full power over society when religious leaders — through rituals and myths — convince the people that the divide between those who merit food and those who do not is of divine rather than human origin”; and “the distinction between good and evil determined who merited food and who did not.”

This is a book that deserves serious study, whether one accepts all of Gustafson’s claims or not. Nearly every person in the world participates in and is affected by the global economy in some manner, and few ever give any consideration at all — much less serious consideration — as to how we are affected and what the costs of our participation actually is.

This book provides us with an opportunity to have a serious and necessary conversation about this topic.

***

Mulhall is a catechist. He lives in Laurel, Maryland.

PREVIOUS: ‘My Big Fat Greek Wedding 2’ lacks zest of the original

NEXT: New program helps girls embrace their femininity

Share this story