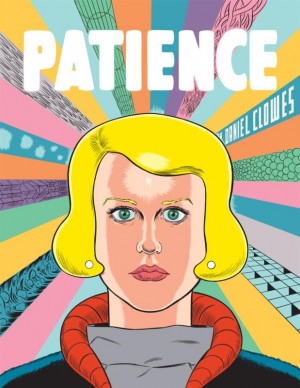

This is an image from the graphic novel “Patience,” which features a time traveler whose goal is to prevent the murder of his pregnant wife. (CNS photo/Fantagraphics)

NEW YORK (CNS) — If you could go back and change the past, would you do it?

That question has become a ubiquitous pop-culture trope, from the “Back to the Future” film trilogy to the CW’s TV series “The Flash,” named for a superhero so speedy, he defies the clock. There’s also Stephen King’s “11.22.63.” King’s 2011 novel, in which a character jumps back decades to try and prevent the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, has been adapted into a miniseries on Hulu.

The latest to delve into this intriguing theme is cartoonist Daniel Clowes. His new graphic novel, “Patience” (Fantagraphics), features a time traveler whose goal is to prevent the murder of his pregnant wife.

It must be said up front that “Patience,” which features considerable violence, sexual content and salty dialogue, is not at all suitable for children — and may not be to the liking of every grownup.

“Patience” does, however, carry an interesting and even moral message. It tells the story of the title character and of her husband, Jack.

When the book opens, Jack has just learned that Patience is pregnant. The couple is joyful at the news, but also anxious. As bohemian artists, how will they manage to support a child?

[hotblock]

With this concern in mind, Jack takes a crummy job handing out fliers. At the end of his very first day at work, however, he returns home to find his slain wife lying lifeless on the floor of their apartment.

The crime shatters Jack. Seventeen years pass, the case still unsolved, and Jack refuses any kind of intimacy with another woman. To do otherwise, he’s convinced, would be to betray Patience. He still feels that there “may be some little piece of her, some cell left on my skin.”

Seizing the opportunity to acquire a time machine, Jack goes back to Patience’s youth, attempting to thwart her various enemies in case one of them turns out to be her killer. It’s an admittedly contrived setup. But the value of “Patience” lies in the use Clowes makes of this somewhat hackneyed premise.

His goal is not simply to recount an adventure or craft a noir-style detective story — although elements of both those genres are present. Instead, Clowes provides a meditation on the pull of grief and how we can be undone by refusing to accept the nature of our fallen world.

The great Catholic author G.K. Chesterton observed that a sane man believes in both fate and free will. Jack, however, attempts to use the latter to change the former. The result is a physical and spiritual deterioration that mirrors Jack’s psychic free-fall.

Jack is an unlikable character, not so much an anti-hero as an outright jerk. He’s given to anger and outbursts of violence.

He’s also selfishly single-minded in his refusal to accept his wife’s death. This self-centeredness starts to cost him, as his interventions in the past begin to alter history in a way that could potentially prevent him from ever meeting Patience in the first place.

Clowes, who became well known in the 1980s for his comic book “Eightball,” is mostly a cynic, satirizing everything from hipster culture to science fiction and organized sports. Yet he’s also capable of softness and genuine pathos, as he demonstrated with stories like “Immortal, Invisible,” “Like a Weed, Joe” and “Ghost World.” (The last of these tales was adapted into a feature film in 2001).

His writings often depict lonely yet acutely intelligent outsiders who mock both their own situations and the culture at large. They’re also self-aware enough to recognize the serious flaws within. The artwork is gorgeously colorful but characters are drawn realistically, with acne, bad hair or ugly faces.

In the case of “Patience,” Clowes combines his sober realism with elements of horror and science fiction, as Jack begins to feel pulled apart by his journeys through time.

Our spouses, Clowes seems to suggest, had a past before they had us, and the pain and tragedy that may have been involved in that history make up integral features of the path that brought them into our lives. If we attempt to change that legacy, we could be unsettling our own futures.

In other words, and to give that sentiment a Catholic spin, there may be something necessary — and redemptive — about suffering.

The graphic novel contains occasional violence, some of it gory, and frequent rough language. The Catholic News Service classification is A-III – adults. Not otherwise rated.

***

Judge reviews comic books and video games for Catholic News Service.

Share this story