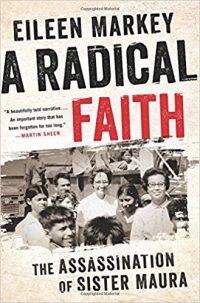

“A Radical Faith: The Assassination of Sister Maura”

“A Radical Faith: The Assassination of Sister Maura”

by Eileen Markey.

Nation Books (New York, 2017).

320 pp., $26.99.

On Thursday, Dec. 4, 1980, the bodies of four women were found in a shallow roadside grave in El Salvador. It became clear after the autopsies that two of them had been raped before being murdered. There were over 8,000 murders that year in El Salvador, but these four victims stood out because three of them were Catholic nuns, the fourth was a lay missionary and all of them were Americans.

“A Radical Faith” tells the story of the eldest victim, Sister Maura Clarke, who was a Maryknoll nun. She had been in El Salvador only four months, but she had been a missionary sister serving in Nicaragua for 20 years.

“A Radical Faith” is the story of her journey from a tightknit Catholic community in the Rockaway area of New York City to the jungles of Nicaragua and El Salvador. But it is also the story of a woman being radicalized by witnessing the suffering poor people at the hands of two corrupt, right-wing dictatorships armed and supported by the United States. Sister Maura was not content to serve the poor by day and live in relative comfort with her sisters in the convent by night; she needed to live like the poor in order to serve them.

[hotblock]

Born Jan. 13, 1931, Maura Clarke was the eldest child of her parents, John and Mary, who had both participated in the rebellion that followed the division of Ireland, before emigrating to the U.S. The family moved often when Maura was a girl depending on the state of their finances, but their moves were all near or in New York City.

She attended Catholic schools and graduated from high school — usually the end of formal education for girls of her lower-middle-class background. One route to a college education and an opportunity to see the world beyond Brooklyn was to become a nun. Clarke chose the Maryknoll Sisters because they were well known for their missionary work overseas.

When Sister Maura entered the order in 1950, novices lived by a strict schedule of individual and corporate prayer. Full habits were worn and visits from family were severely limited. When she had completed her two and a half years as a novice, she was sent to teach in a school in a poor neighborhood in the Bronx.

Sister Maura became known for her warmth and deep empathy with the schoolchildren. At times, her attention to individual students interfered with her work as a teacher and her life as a religious. She served in the Bronx until 1959 when she finally was offered a foreign posting in Nicaragua. She would spend most of the next 20 years teaching and working with poor people — first in a remote village, Siuna, and then in the capital city of Managua.

Sister Maura’s first years in Nicaragua also were the years of the Second Vatican Council, which would upend the Catholic Church and its many religious orders. The Maryknoll Sisters made their habits more practical, individual sisters had greater autonomy in choosing their ministries, and families could be visited when a sister chose to visit them.

[hotblock]

Vatican II also changed how Sister Maura viewed her mission in Nicaragua. She grew to believe that religious instruction in the Catholic faith had to be based on the experiences of the poor and drawn from their experience of faith. She would encourage women to form their own communities of faith to learn for themselves that they were equal members of the body of Christ.

She learned that the poverty in which most Nicaraguans lived was a result of the unequal distribution of wealth to a few closely connected to the regime of Anastosio Somoza. She also learned that the aid coming from the U.S., especially after the massive earthquake in Nicaragua in 1972, never reached those in real need. The center of Managua was left flattened after the temblor and not rebuilt because money flowing to Nicaragua would be used to buy weapons for the governmental forces to fight the leftist rebellion. Sister Maura’s politics followed her religious faith as she increasingly identified with the struggle of poor people to throw off their oppressors. Her convictions put her at ever greater risk.

“A Radical Faith” brilliantly follows Sister Maura’s deepening identification with the poor, which would lead, ultimately, to her murder 20 years after she arrived in Central America. She would die a martyr, honored both in Nicaragua and the United States.

Martyrdom as an ideal has not been emphasized in Catholic teaching in our time as it was in the years of Sister Maura’s education. The idea of sacrificing one’s life for one’s beliefs has been tainted by years of terrorism carried out by suicide bombers claiming they are martyrs.

There are those who claim Sister Maura died because she was associated with leftist rebels, not because of her Christianity. Others like Eileen Markey, the author of “A Radical Faith,” would argue that she did not separate her political beliefs from her faith and that her murder was the death of a martyr.

It is hard to imagine that another book as deeply researched, fascinating to read and more moving than “A Radical Faith” will come along soon. “A Radical Faith” deserves a wide readership.

***

Yearley is a graduate of the Ecumenical Institute of St. Mary’s Seminary and University in Baltimore.

PREVIOUS: ‘Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2’ is beyond the orbit of younger viewers

NEXT: Entree of morality in ‘The Dinner’ proves too tough to cut through

Share this story