(CNS)

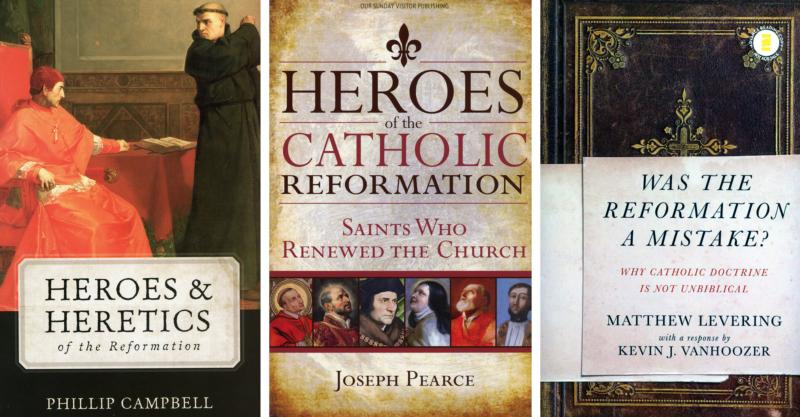

“Heroes of the Catholic Reformation: Saints Who Renewed the Church”

by Joseph Pearce.

Our Sunday Visitor (Huntington, Indiana, 2017).

176 pp., $16.95.

“Heroes & Heretics of the Reformation”

by Phillip Campbell.

Tan Books (Charlotte, North Carolina, 2017).

324 pp., $27.95.

“Was the Reformation a Mistake? Why Catholic Doctrine Is Not Unbiblical”

by Matthew Levering.

Zondervan (Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2017).

240 pp., $27.95.

Five hundred years later, the effects of the divorce initiated by Martin Luther are still being worked out.

As Catholics, we can acknowledge the excesses and irregularities of the medieval church while mourning the tragic fracturing of Christian brotherhood. But as a trio of new books explore, the way we react to the Reformation, even now, says nearly as much about how we see the church today as it does about the fissures of five centuries ago.

[hotblock]

What is called the “Reformation,” of course, was a multifaceted development throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, and understanding it requires having a handle on the personalities, environments and doctrinal questions that fractured the church. In “Heroes & Heretics of the Reformation,” Phillip Campbell offers a concise, readable overview of the tumultuous history.

While the stories of saints in the book are told winsomely and largely without hagiography, the treatment of figures in the Protestant movement are recounted especially well. Campbell, an author of Catholic textbooks, offers a frank yet fair refresher on familiar names like Luther and John Calvin, continuing on to some of less-remembered figures such as Thomas Muntzer, John Knox and Thomas Cranmer.

Despite citations of Wikipedia and more than a few references to imagination rather than the historical record, the book is an admirable primer for those who have forgotten — or never learned — about the men and women who demonstrated resolve, cunning and passion on every side of the divide that would tear Christendom asunder.

Joseph Pearce’s “Heroes of the Catholic Reformation” treads similar ground more reverently, offering laudable stories of heroic virtue. He also takes pains to make “parallels between Tudor England and the secular fundamentalism of our own age … in the hope that it will inspire similar holiness and heroism today.”

The stories are artfully and passionately told, with an undergirding thesis that the beauty and heroism of figures such as Sts. Thomas More, John Fisher, Edmund Campion and the rest were the “real” reformation. These saints brought a desperately needed energy, discipline and reform back to the church, Pearce says, and the idea that Luther and Calvin’s actions were a “reformation” is in fact an “utter misnomer.”

For a substantive treatment of these theological debates, Matthew Levering, chairman of the theology department at the University of St. Mary of the Lake at Mundelein Seminary, asks the question: “Was the Reformation a Mistake?”

[tower]

Despite his book’s provocative title, Levering is no bomb-thrower; he holds that “the Reformers made mistakes, but that they chose to be reformers was not a mistake.” Levering holds that the divide created by Luther and Calvin was tragic yet in some respects necessary.

However, he holds that many of the theological arguments marshaled by the Protestant reformers can be answered with a tradition-informed reading of the Bible that, like the meal at Emmaus, receives teachings that cannot be understood until grace reveals them.

Levering aims to put forth rationales for Catholic doctrine that might prove appealing to a reader who looks only for biblical authority. In this, he aims low — not seeking to proves the church’s position outright, but only to defend the plausibility of Catholic teaching on familiar apologetical ground such as Mary, the papacy and the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

Each chapter recaps Luther’s original objections, then offers a reflection, not even necessarily an argument, on how we can understand the church’s understanding as addressing those objections or why the objections might result from misapprehensions.

He hits the mark he sets for himself, while generously offering space for a friendly rebuttal from Protestant theologian Kevin Vanhoozer. Levering is a modest yet knowledgeable guide, content to rest in offering plausible defenses, instead of seeking persuasive ones.

Levering sees the Reformation through the lens of a theologian; Campbell, as a historian; Pearce, as a historically informed advocate for a renewed spirit of engagement and reform. All three are crucial for understanding where we’ve been, and suggest different ways of addressing the Reformation’s legacy today.

Whether or not Pearce is right that “we live in dark and doom-laden days,” understanding the causes and faces that energized the Reformation better helps us understand our own deposit of faith. Pearce, with his explicit parallels between the hostility of Tudor England and contemporary battles over religious liberty, would suggest a need for greater emphasis on the heroic virtue needed to stand up in the face of tyranny.

Levering’s book might awaken a re-examination of the doctrinal differences that keep Christian unity an aspiration. Campbell’s lens reminds us that the church has withstood much against attacks from both without and within.

The most appropriate approach to the moment we live in now, where the church’s challenges are less open persecution than the gradations of shifting social pressures and changes, may not be any of the three.

But they remind us that after 500 years of reform, reaction and resistance, the 93 theses and all that followed remain a vivid scar on the body of Christ, and how we see that scar — as a reminder of past pain, a mark in need of present healing, a summons for future courage or all three — indelibly shapes what we see as the church’s mission.

***

Brown is a graduate student at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School for Public and International Affairs.

PREVIOUS: ‘The Miracle Season’ is a true-life, tear-jerking inspiration

NEXT: ‘A Quiet Place’ tells of silent resistance to scary tyranny

Share this story