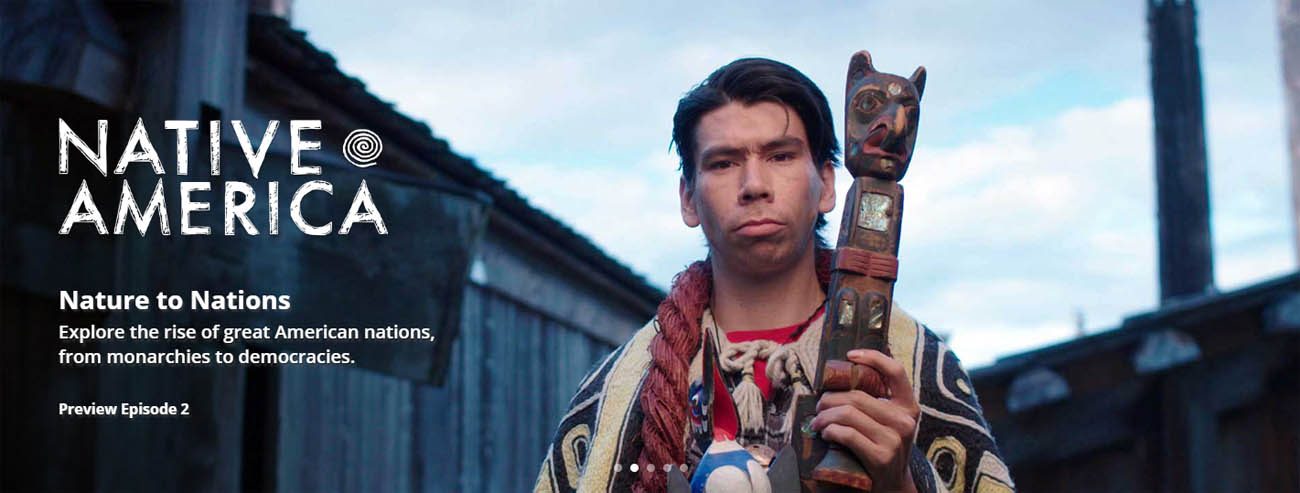

NEW YORK (CNS) — Mohawk tribe member and former lead guitarist of the storied rock group the Band Robbie Robertson narrates the new PBS documentary “Native America.”

The admirable, edifying, but only fitfully engaging four-hour film premieres Tuesday, Oct. 23, 9-10 p.m. EDT. The series continues Tuesday, Oct. 30, 9-10 p.m. EDT and concludes Tuesday, Nov. 13, 9-11 p.m. EST.

Midterm election coverage Nov. 6 explains the scheduling gap. Broadcast times may vary in some markets.

With “modern scholarship and native knowledge,” the program examines and affirms Native Americans’ way of life, which is “intimately connected to earth, sky, water and all living things” as manifest in the ancient cities they created, and the traditions they preserve today.

[hotblock]

Executive producer and director Gary Glassman employs vivid computer animation, native storytelling, time-lapse cinematography, and commentary from scholars and tribal members to enhance the show. Numerous Native American musicians, including the Grammy Award-winning performer Joanne Shenandoah, contributed to the soundtrack, which also enriches “Native America.”

Most of the history the film details involves lost civilizations many viewers may not know ever existed. A thousand years ago in a remote canyon in New Mexico, for instance, Native Americans built Chaco, one of that era’s largest North American cities.

Similarly, around the year 1100 on the opposite shore of the Mississippi River from present-day St. Louis, a thriving indigenous city named Cahokia boasted a population of 30,000, making it larger, according to the filmmakers, than 12th-century London. Cahokia was built on earthen mounds 10 stories high. No one has quite pinpointed who erected these impressive structures, but their spirituality informed their industry.

Whichever pre-Columbian community was responsible for creating Cahokia, raising high buildings reflected, according to Choctaw tribe member Harold Comby, their desire to get “closer to the creator.” Finding their “centerplace” in the universe amid the “sacred earth” was a unifying spiritual principle for Native Americans in general, in the documentarians’ view.

It’s interesting to note that the heyday of Cahokia roughly corresponded to the period in Europe that saw the rise of Gothic architecture — which can be analyzed as demonstrating similar aspirations, within a Christian context, to those Comby identifies.

[tower]

In the case of the Haudenosaunee — more familiarly known as the Iroquois –- a confederacy of five New York State tribes, what they learned about effective farming was translated into methods of community organizing and self-governance.

In their “three sisters” agricultural practice, corn, beans and squash grew harmoniously together. By analogy, they saw that, like the corn, some in their community stood tall, while others, in imitation of the beans, provided support. Still others, in the manner of the squash, laid themselves down to protect the vulnerable.

Community members adopted these varied roles in the Haudenosaunee’s governing councils, held in the longhouses from which the tribes took their collective name. Established as early as 1150, these assemblies formed the basis for one of the world’s oldest democracies, a structure of government that some historians believe influenced the provisions of the U.S. Constitution.

Given its discussions of such mature topics as human sacrifice, war, racism and genocide, “Native America” is not suitable for youngsters. Though it’s safest for adults, some parents may consider the program’s educational value sufficient to allow older teens to watch.

Viewers of whatever age will find their attention engaged by the informative nature of the first three episodes. But a slow pace, a lack of tension in the narrative and some repetitious material may cause a gradual falling off of interest as the series approaches its end.

“Native America” also can be faulted for an oversimplified presentation of the Catholic Church’s role in the Age of Exploration. While the papacy both encouraged and regulated the conquest of the New World carried out by Spain and Portugal, in the obvious hope of converting the natives of the conquered lands, decrees of the Holy See also denounced the abuse of indigenous people.

A 1537 apostolic brief, for instance, imposed the penalty of excommunication on anyone enslaving or despoiling Native Americans. Though this measure was eventually relaxed under pressure from the Spanish crown, the underlying spiritual teaching that all human beings were equal in the sight of God remained in place.

Indeed, the belief, then held by many in Europe, that the natives of the Americas were less than fully human was denounced as nothing less than satanic by Pope Paul III.

Successfully highlighting how indigenous people have transferred their sustaining traditions from generation to generation, “Native America,” despite its shortcomings, merits a large audience.

***

Byrd is a guest reviewer for Catholic News Service.

PREVIOUS: ‘Gosnell’ dramatizes Philadelphia’s ‘serial killer’ abortionist

NEXT: Cartoonist’s comics lighthearted but aim to provoke thought about faith

Share this story