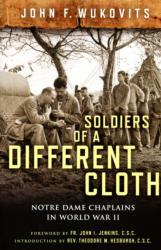

“Soldiers of a Different Cloth: Notre Dame Chaplains in World War II”

“Soldiers of a Different Cloth: Notre Dame Chaplains in World War II”

by John F. Wukovits.

University of Notre Dame Press (Notre Dame, Indiana, 2018).

381 pp., $35.

This riveting account of the heroic contributions of 35 chaplains and missionaries during World War II is nearly impossible to put down. The author, John F. Wukovits, is a renowned military historian who melds rigorous research with expert storytelling. The result is an inspiring and richly detailed narrative that reveals the challenges that these religious — priests along with some brothers and sisters of Notre Dame’s Congregation of Holy Cross — faced.

The youngest was 22 and the oldest 53, but most were not spared the rigors of battle. They marched alongside the troops in the Bataan Death March, parachuted with the 101st Airborne into Normandy on D-Day, and endured Belgium’s freezing cold in the Battle of the Bulge. Those captured alongside the young men they served were also imprisoned in hellish conditions in Germany and Japan. At the end of the war, they beheld the unspeakable scene at Dachau and prayed over the dead piled high like cordwood in train cars.

These extraordinary men and women come alive on every page, thanks to Wukovits’ exhaustive archival research at Notre Dame and several other institutions. He also conducted interviews with several key figures who knew the chaplains, including the late Holy Cross Father Theodore Hesburgh, the longtime Notre Dame president.

[hotblock]

Among the memorable chaplains Wukovits highlights is Holy Cross Father Joseph D. Barry, a gritty son of Irish immigrants from Syracuse, New York, who stood just 5 feet 3 inches tall. Although an excellent athlete, he was challenged by the arduous physical training he and the other chaplains endured to equip them to handle the same rigors as the young men to whom they ministered. Wukovits recounts how Father Barry wrote to his supervisor back at Notre Dame, “This business of marching 20 and 30 miles a day, wading through swamps, certainly gives a fellow a tiger appetite and the will to fall asleep while walking.”

In Italy in July 1943, Father Barry accompanied his young soldiers into combat. While they carried rifles and hand grenades, he “carried only his khaki uniform, his stole, and his prayer book.” Ignoring German sniper shots all around him, he crawled among the fallen men, checking to see what religion was listed on their dog tags. He would “either hurriedly hear confession and give absolution to the Catholics or say a quick prayer for the non-Catholics before moving on,” Wukovits writes. “He dropped low to the ground to press his ear next to the mouths of the injured and dying men, straining to hear the whispered words amid the din of shell bursts, machine guns, and shouts.” The Army honored his bravery with the Silver Star.

Like Father Barry, Father Francis L. Sampson undertook the grueling physical training required for the chaplaincy. But because he hoped to serve with paratroopers, he had to master jumping from an airplane “toward trees that now appeared to be the size of toothpicks.” He overcame considerable anxiety to accomplish this feat and, as “Paratrooper Padre,” went on to land with the troops on D-Day at Normandy, ultimately earning both a Bronze Star and the Distinguished Service Cross.

Like his fellow chaplains, Father John E. Duffy chose to spend his time at the front with the infantry, rather than behind the lines. In the Philippine jungle, the diocesan priest from Lafayette, Indiana, tried to offer Mass in a different location every day, the better to reach more soldiers. Wukovits tell us that “his churches ranged from small huts to open fields, where he celebrated Mass on altars made from used crates and broken wooden tables.”

His days were packed with hearing battlefield confessions of young men, administering last rites, and burying the dead and marking their graves. He also “delivered orders under fire from commanders to troops, walked miles through the heavy jungle to join men at the front, and used a shortwave radio to relay hurried messages from soldiers to family back home. He was parent, friend, and confidant to young men in their time of greatest peril.” Even after being wounded (and honored with the Purple Heart), he would not leave his men.

[tower]

During the Bataan Death March, Father Duffy was bayoneted and left for dead. But sympathetic Filipinos rescued him, dragging his inert body into the woods. He recovered, but eventually the Japanese captured and sent him to the infamous Bilibid prison camp in the Philippines, where he endured myriad hardships that included beatings and starvation. From there, it was a transport voyage on a so-called “hell ship” to a prison camp in Japan. Along the way, the priest said Mass whenever he could and administered last rites to the many dying. “I did what I could for each regardless of his faith,” Father Duffy said in an interview right after the war from which Wukovits quotes, “and a look of ineffable peace came to the face of many a tortured soul in that last bitter hour on earth.”

This passage underscores the impact that these religious had on the troops. As the author demonstrates throughout, they provided incalculable spiritual direction and comfort. They helped maintain the young soldiers’ morale, befriending and counseling them in the most terrifying time of their lives.

Wukovits adeptly weaves in the chaplains’ link to Notre Dame. In their letters to their superior in South Bend, Indiana, they often inquired about the campus and the football team. This increases the book’s appeal to Notre Dame alumni and fans, but it is never overwhelming.

Meticulously researched and documented, the book includes a detailed bibliography and an appendix that presents photos and information about these 35 individuals, including their ages on Dec. 7, 1941, when the United States entered the war after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. A chronology and maps, as well as numerous black and white photographs, enrich the narrative. “Soldiers of a Different Cloth” is essential and thoroughly engaging reading for anyone interested in World War II. Wukovits makes a major contribution to our understanding of that war by showing it through the little-studied perspective of these brave chaplains and missionaries.

***

Roberts directs the journalism program at the University at Albany and has written and co-edited two books about Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker.

PREVIOUS: Book shows human faces of IS victims, atrocities of Islamic caliphate

NEXT: ‘Vice’ does a gleeful, nuance-free hatchet job on Dick Cheney

Share this story