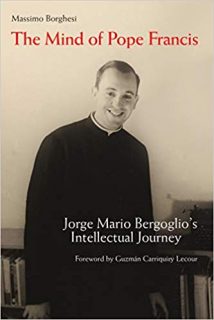

“The Mind of Pope Francis: Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s Intellectual Journey”

“The Mind of Pope Francis: Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s Intellectual Journey”

by Massimo Borghesi.

Liturgical Press (Collegeville, Minnesota, 2018).

310 pp., $29.95.

In the age of the global papacy, the current occupant of the chair of St. Peter often gets boiled down to a simple caricature. St. John Paul II? An anti-communist celebrity. Pope Benedict XVI? A doctrinaire “rottweiler.” Pope Francis? Light on theology, heavy on lived example.

Each of these shorthand descriptions captures some glimmer of truth, but all flatten the real bishop of Rome into a simple, two-dimensional object that can be easily slotted into the theological or political controversies of the moment. The current Roman pontiff, with his flair for the dramatic and emphasis on a “church that goes out to the margins,” is often characterized as being uninterested in theology or dogma.

As “The Mind of Pope Francis,” a new biography by Massimo Borghesi, illustrates, this depiction does the man born Jorge Bergoglio short shrift. As the book’s subtitle — “Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s Intellectual Journey” — indicates, this is not a light read. Readers looking for an accessible introduction to the formative experiences that led Bergoglio to the papacy would be better served by Austin Ivereigh’s “The Great Reformer: Francis and the Making of a Radical Pope.”

[hotblock]

But for those interested in the intellectual framework that undergirds Pope Francis’ theological outlook, Borghesi paints a picture that is rigorous and sympathetic, suggesting a richness and complexity to a distinctly Bergoglian theology.

Borghesi’s book makes the claim that even in his stated preference for simplicity, Pope Francis is grounded in a complex, deep-rooted theology that is heavily indebted to figures from his formative years in Buenos Aires, particularly Alberto Methol Ferre, the eclectic Uruguayan journalist and writer to whose memory Borghesi dedicates the book.

Methol Ferre’s influence is felt heavily throughout the dense theological exploration, and never more than the section that delves into the famous concluding statement of the Latin American bishops’ council (known as CELAM, the acronym for its Spanish name) general conference in 2007, held in Aparecida, Brazil. The document, worked on heavily by then-Cardinal Bergoglio, remains a touchstone of the now-pope’s thinking, with its repeated call for a “continental mission,” a church that goes out in search of ways to proclaim the Gospel to all.

“Aparecida,” writes Borghesi, “was the ‘baroque’ synthesis of tradition and modernity imagined by Methol Ferre, of traditional faith and new proclamation. It corresponded fully to the “coincidentia oppositorum” (unity of opposites) desired by Bergoglio.”

Borghesi identifies an intellectual thread emphasizing the competing tensions of “polarity” forming this unity of opposites woven throughout Bergoglio’s, and now Pope Francis’ writing. The title of Bergoglio’s unpublished doctoral thesis points to the importance of this concept in Bergoglian thought: “Polar Opposition as Structure of Daily Thought and Christian Proclamation.”

Borghesi’s interpretation is given some weight by being influenced by four audio-recorded messages sent by the pope to the author, walking through his thinking and influences. While excerpts from these responses appear throughout the book, it would have been interesting to read fuller transcripts, perhaps as an appendix.

[tower]

Four theological principles mark the pope’s thinking, according to Borghesi — unity is superior to conflict, time is superior to space, the whole is superior to parts and reality is superior to ideas. Seeing these through-lines fleshed out in detail helps illumine some of the pope’s actions that have inflamed the most controversy — the debates over Communion for the divorced and remarried, for example.

Again, the book is clearly intended for academic audiences, or at least those conversant in the debates that rage through academic theology. Sprightlier prose and more synthesis, rather than recitation of others’ work, would have made a more generally accessible read. A chapter at the end explicitly traces the tension between Bergoglio’s thinking and what Borghesi calls “American Catho-capitalism.” More in that vein would have been appreciated, but that would have also been a different book.

Pope Francis will never follow in Pope Benedict XVI’s steps in writing a trilogy of scholarly exegesis, tracing the life of Jesus from infancy to Holy Week, nor, one suspects, will his papal teaching on social and economic questions likely be as influential decades hence as St. John Paul’s writings continue to be.

But there are many gifts, yet the same Spirit, and comparing his theological output against those two giants is not meant to diminish his own contribution and gift of taking the theological and philosophical teaching of the church and translating it into terms and actions that are recognizable to everyday family life.

His namesake’s advice to preach the Gospel at all times, and use words when necessary, remains a hallmark of the current pontiff’s style.

Borghesi’s attempt to show that a more rigorous intellectual framework undergirds the off-the-cuff style is a worthwhile read for serious Francis interpreters, but hints of Bergoglio’s intellectual approach may be gleaned more accessibly with a careful study of the Aparecida document or his papal writings themselves.

***

Brown is a graduate student at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

PREVIOUS: Players of ‘Dragon Quest Builders 2’ build in a world where it’s banned

NEXT: Rhode Island pastor competes on ‘Worst Cooks in America’ reality TV show

Share this story