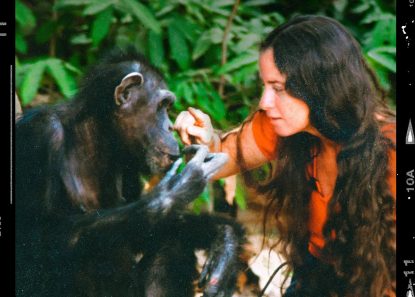

This is the TV poster for “Lucy, the Human Chimp” streaming on HBO Max. (CNS photo/HBO Max)

NEW YORK (CNS) — A primatologist’s highly unusual interaction with the species of the title is recounted and partly dramatized in “Lucy, the Human Chimp.” The 70-minute documentary, which is streaming now on HBO Max, contains undeniably touching moments. But it may leave viewers feeling baffled since it ultimately raises more questions than it answers.

A collaboration between KEO Films and Britain’s Channel 4 network, the film was written and directed by Alex Parkinson.

In 1976, 25-year-old Janis Carter (Lorna Nickson Brown), a University of Oklahoma graduate student in psychology, answered a help wanted ad that changed her life. Her new employers, researchers Maurice (Matthew Brenher) and Jane (Jacinta Mulcahy) Temerlin, introduced her to Lucy, a 12-year-old chimpanzee they were raising as “their daughter.”

The Temerlins had discovered Lucy at a Florida roadside zoo when she was only two days old. Intent on studying the age-old issue of nature versus nurture, they took her home and, employing sign language, taught her 120 words.

[hotblock]

Carter’s duties were initially limited to cleaning Lucy’s cage and feeding her. But she eventually defied these strictures and bonded with her charge through mutual grooming.

Before long, however, the Temerlins decided that continuing to domesticate Lucy was not a viable option. Instead, they prepared to relocate her to western Africa and release her in the Gambia’s Abuko Nature Reserve.

Retraining Lucy to live in the wild, though, was likely to prove challenging. Among other things, the ape had acquired a fondness for eating food from Dairy Queen and drinking gin and tonics.

Having deposited Lucy in her new environment, the Temerlins returned to the U.S. But, sensing that the primate wasn’t herself, Carter remained behind. This not only led to a deepening of her relationship with Lucy but culminated in her living among — and becoming the leader of — a group of 11 chimps, a situation that lasted for more than six years.

As will already be obvious, Parkinson’s movie is ambiguous in its presentation of the proper relationship between human beings and animals. Additionally, it features discussions of mating, predatory behavior and thorny ethical issues, making it inappropriate for kids but acceptable for older teens as well as grown-ups.

Reenactments of real-life events often feel false and ineffective. Here, though, the extended scenes of Carter interacting with the chimps prove immersive, giving viewers the sense that they’re living with the naturalist in real time.

Philosophically, on the other hand, the film is far from satisfying.

The Temerlins’ exploitation of Lucy is troubling. But so, too, is Carter’s assertion that, following her decision to remain in the Gambia, she and Lucy “began to know each other as people.” Along the same lines, she maintains that her interaction with Lucy and the other chimpanzees “fulfilled all the human needs I had for social contact.” That seems a bizarre claim at best.

In the end, “Lucy, the Human Chimp” is certainly interesting — but also murky and unsettling. As a result, many viewers may come away from it not quite knowing what to make of Carter’s remarkable story.

***

Byrd is a guest reviewer for Catholic News Service.

PREVIOUS: Adults behaving badly casts specter on child in ‘Separation’

NEXT: A look at labor justice through a Catholic lens

Share this story